Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis, June, 2021

© 2021 Regents of the University of California

The University Grape and Wine Program, 1879 to 1950

The University of California launched its grape and wine programs beginning in the 19th century when the commercial industry in the state was new and unstructured. Colonists, growers and nurserymen had imported many important wine grape varieties to North America by the 1870’s. However, information on the suitability of grape varieties for particular climates within California and application of scientific methods to wine-making practices were not yet developed in the state. The University became proficient at both issues.

Early explorers and colonists to North America found an abundance of native grapes growing wild throughout the continent. The colonists in the eastern, middle and southern regions of the continent found that they preferred the familiar flavors of the grapes from the wines of their European homelands and imported varieties of those grapes, known as Vitis vinifera. The colonists’ early efforts to cultivate vinifera varieties in America beginning around 1621 proved unsuccessful due to unsuitable climatic conditions and susceptibility to diseases. 1 Liberty Hyde Bailey, “Rise of the American Grape”, Sketch of the Evolution of our Native Fruits, The MacMillan Company, New York and London (1898): 1-21; U.P. Hedrick, The Grapes of New York (Fifteenth annual report, Dept. of Agriculture, State of New York), Albany, Part II: 1-564.

Vitis vinifera (the “European grape”) is defined in General Viticulture as the “species from which all cultivated varieties of grapes were derived before the discovery of North America”. 2 A.J. Winkler, J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.A. Lider, General Viticulture (Regents of the University of California, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1962, 1974): 1. The species originated in Asia Minor and migrated to Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. Popular vinifera varieties were adaptable and diverse and evolved from the wild vine which naturalized in the countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. 3 Bioletti, Frederic, paper entitled “Viticulture on the Pacific Coast”, prepared for the International Congress of Viticulture, San Francisco, 1915, accessible in Bioletti collection D-363, folder 4: 17, at Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis. Vitis vinifera is the grape species used to make quality wines in Europe for centuries. Although the West Coast of the United States had its own indigenous grapevine varieties, such as Vitis girdiana and Vitis californica, the major story line for viticulture in that region proved to be the affinity of Vitis vinifera for the western climate. Attempts at growing vinifera grape varieties in California were successful from the outset since conditions mirrored those of the native habitat for the species.

Frederic T. Bioletti, the first U.C. Professor of Viticulture, explained that climatic conditions in the Pacific Slope region are those preferred by vinifera grapes – sufficient heat during the growing season; dry air during the hotter part of the growing season; absence of winter cold sufficient to kill the dormant vine; and rarity of frosts during the growing season. He observed that the species was characterized by vigor, fruitfulness, wide adaptation to diverse soils and amenability to simple methods of pruning and cultivation. The intolerance of vinifera to all but a narrow range of climatic conditions did not pose a significant obstacle in the Pacific Coast region because the fungus diseases that threatened the species do not exist to a significant degree. 4 Frederic T. Bioletti, paper entitled 'Viticulture on the Pacific Coast', presented at the International Congress of Viticulture in San Francisco, 1915; accessible in the Bioletti collection D-363, box 4: 17, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis.

Pre-U.C. viticulture in California

The history of viticulture in California between 1770 and 1830 was closely associated with the development of the Spanish missions from San Diego (1769) north to Sonoma (1833). Mexican commander General Mariano Vallejo wrote that Franciscan Father Junípero Serra first brought grapevines to Mission San Diego in 1769.The first clear documentation regarding planting grapevines in the Mission system was a reference to Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1779. 5 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 238-245 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); A.J. Winkler, J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.A. Lider, General Viticulture (Regents of the University of California, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1962, 1974): 1-2. Mission San Gabriel (established in 1771) eventually became the center of grapevine activity due to its large size, central location and favorable soil and moisture conditions. The vineyard at San Gabriel was referred to as the “mother vineyard (viña madre)”, from which material was distributed to the other missions. Wine was also made at Missions in southern California. 6 A.J. Winkler, J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.A. Lider, General Viticulture (Regents of the University of California, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1962, 1974): 1-2.

Evidence supports the presence of named vinifera varieties such as Muscatel and Malaga in the Mission vineyards. However, the predominant grape variety in California from the early Mission period through the Gold Rush (1850) was a variety named Mission (Misión), imported to the New World in the 1500’s, probably in the form of a seed rather than as a cutting. 7 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, p. 209, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000.

More than 400 years later in 2007, genetic analysis showed that the variety Mission (UC Davis plant material) and 49 other ancient American accessions such as País (Chile) and Criolla chica (Argentina) shared identical DNA with the Spanish variety Listán Prieto. Listán Prieto was an important cultivar in Castilian viticulture and was introduced to the Canary Islands in the 16th century. 8 Alejandra Milla Tapia, José Antonio Cabezas, Felix Cabello, Thierry Lacombe, José Miguel Martínez-Zapater, Patricio Hinrichsen and María Teresa Cervera, “Determining the Spanish Origin of Representative Ancient American Grapevine Varieties”, Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 58(2): 242-251 (2007).

In those early years, Mission was readily available, prolific, and widely planted throughout the state of California. 9 H.M. Butterfield, “History of the Grape Industry in California”, The Blue Anchor, December 1969: 21-27 [reprint of 1938 article]. The Mission vine was notable for its vigor and hardiness, resulting in “specimens of enormous size”. 10 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 234-241 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); A.J. Winkler, J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.A. Lider, General Viticulture (Regents of the University of California, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1962, 1974): p. 4. For example, one huge specimen from Carpenteria produced eight tons of fruit in 1893 when it was 51 years old. 11 A.J. Winkler, J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.A. Lider, General Viticulture (Regents of the University of California, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1962, 1974): p. 4; H.M. Butterfield, “The builders of California’s Grape and Raisin Industry”, The Blue Anchor, pp. 21-27, December 1969. The variety was the most popular grape in California through the Gold Rush era. 12 Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 2, 23 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951).

Early U.C. reports indicated that Mission wine achieved a high sugar content but was deficient in color and acidity and lacked varietal character as a dry table wine. 13 Amerine, Maynard. “An Introduction to Pre-Repeal history of Grapes and Wine in California”, presented at the Second Annual Meeting of Library Associates, University of California, Davis, delivered November 10, 1967, reprinted from Agricultural History, vol. XLIII, 2, April 1969. While Mission did not produce acceptable dry wines, the variety was suitable for sweet dessert wines. Mission is still considered significant as a sweet or dessert wine cultivar. 14 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 234 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989).

Since the early 1960’s, the Department of Viticulture & Enology at U.C. Davis has had a tradition of planting a Mission vine and growing it out on a large trellis structure somewhere on campus. The Department knew from historical records that unusually large and productive vines existed during the early periods of grape growing in California. No studies had ever been done to that time to determine what factors influenced their development. The vines on campus were planted to give them ample space, adequate trellis support and rigorous crop control. The Department chose the Mission variety since it had been in California for quite some time. 15 A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, with an Introduction by Maynard Amerine, pp. 112-113, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley (copyright by the Regents of the University of California, 1973).

The first such vine known as the “Winkler vine” was budded in 1961 near the Viticulture field house in the Department of Viticulture vineyards in Armstrong Tract south of Highway 80 on Old Davis Road. The planting was dedicated to Department Chair Albert Winkler because of his special interest in the cultivation of the Mission variety. The students took a special interest in monitoring the data for the vine. 16 A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, with an Introduction by Maynard Amerine, pp. 112-113, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley (copyright by the Regents of the University of California, 1973).

When the first vine died from wood rot and eutypa, the Department planted a new “Winkler vine” in 1977 in the Tyree Vineyard on Hopkins Road west of campus. That vine died in 2007 also of wood rot and eutypa. Meanwhile, the Winkler vine site had become a venue for annual Department fundraising dinners. A new “Winkler vine” was planted shortly after 2007 and is now fully established and is expected to fruit in 2021. 17 Email to author from Professor Andrew Walker, Department of Viticulture & Enology, U.C. Davis, June 09, 2021. An adjacent arbor trellis was created when the most recent Winkler vine was planted. The second vine was named the “Olmo vine” and is also expected to fruit in 2021.

FPS Mission selections

Several Mission selections collected from vineyards throughout California are now part of the grapevine collection at Foundation Plant Services (FPS) on the U.C. Davis campus. The University’s foundation vineyard collection was initiated in the late 1950’s and 1960’s. The Mission selections were obtained in 1965 from old vineyards in San Joaquin (Mission FPS 02), Calaveras (FPS 06), Santa Barbara (FPS 07 and 08), and Sonoma (FPS 12) Counties. Two Mission selections (FPS 11 and 13) were collected from the former University of California Sierra Foothill Experiment Station vineyard in 1963 and 1966. In 2013, Deborah Hall, owner of Gypsy Canyon in the Santa Rita Hills, donated a Mission selection which was collected from a very old vineyard planted around 1887 in Santa Barbara County. Ms. Hall has over the years donated Mission cuttings from that same vineyard to assist with restoration of the vineyards at the remaining California missions.The Mexican government secularized the mission system in 1833-1834 and gradually abandoned the mission vineyards. At the time, the vineyard at Mission San Gabriel had 200 acres of grapevines (163,579 vines). 18 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, p. 209, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000; Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 3-4 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951); H.M. Butterfield, “History of the Grape Industry in California”, The Blue Anchor, December 1969: 21-27 [reprint of 1938 article]. The dissolution of the dominant mission system in California in the 1830’s enabled the rise of commercial viticulture and wine-making enterprises beginning in southern California.

In his comprehensive publication A History of Wine in America, Thomas Pinney presents a detailed history of winegrowing in California. 19 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 269, 243-284, 347 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989). Serious efforts to expand the number and quality of European wine grape cultivars beyond the Mission grape and the few other Vitis vinifera varieties were begun in the state between 1833 and 1850. Immigrants from the five major wine making countries of Europe (France, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Germany) settled in California prior to the Gold Rush (1849). Those European immigrants realized that the climate and terroir were favorable for the European grape cultivars.

The earliest efforts were made in southern California, which would maintain supremacy until the 1860’s. Recent immigrant Jean-Louis Vigne imported grape varieties from his native Bordeaux, France, to Los Angeles in 1833; records of the varieties he established and whether they survived do not exist. 20 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, p. 209, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000; Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 246-248 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 9-12 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951). William Wolfskill and Koehler & Frohling were major producers of grapes and wine during that period. 21 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 244-263 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 9-13 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951). Small growers formed cooperatives such as the Los Angeles Vineyard Society (1858 in Anaheim) or the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society (1856 in Sonoma). 22 H.M. Butterfield, “History of the Grape Industry in California”, The Blue Anchor, December 1969: 23 [reprint of 1938 article].

Winegrowing began on a small scale in northern California before the Gold Rush with pioneers such as General Vallejo in Sonoma, George Yount in Napa, Peter Lassen in Tehama and the Wolfskill brothers in Solano. Many of the new European winegrowers settled in the valleys surrounding the San Francisco Bay Area and developed them into important centers of viticulture. Interest soon spread to the San Joaquin Valley and Sierra Foothills. Growers and nurserymen brought many Vitis vinifera varieties into the state between the Mission Era and inception of the viticulture work at the University of California. 23 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 258 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 10-13 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951); H.M. Butterfield, “History of the Grape Industry in California”, The Blue Anchor, December 1969: 23 [reprint of 1938 article].

Although the dominant variety continued to be the Mission grape, California nurserymen and growers began to import better winegrape varieties from Europe in the early 1850’s. Two French immigrants were the first to bring superior varieties to northern California. Nurseryman Antoine Delmas of San Jose imported French wine grapes in 1852, including “Cabrunet”, “Medoc” and “Merleau”. Between 1852 and 1854, brothers Louis and Pierre Pellier imported grape varieties such as French Colombard, Grey Riesling and Folle blanche from France. Prominent winegrape grower Charles Lefranc of Almaden imported French varieties from France in the 1850’s to plant in his vineyards and sell commercially. 24 Charles L. Sullivan, Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present, 2nd ed., p. 136 (The Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, 2008); Sullivan, Charles L., Zinfandel, A History of a Grape and its Wine, pp. 29-30 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, 2003), p. 27; Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine, pp. 86, 188, 255 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). Nurserymen William and George West of Stockton imported grapevine varieties from Boston in 1853. 25 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 263-264 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989) Bernard Fox, superintendent of Hovey & Co. Nursery of Boston, established Stockton Ranch Nursery where he advertised vinifera varieties in 1854. 26 Charles L. Sullivan, Zinfandel, A History of a Grape and its Wine, pp. 27-28 (University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 2003); Lynn Alley and Deborah Golino, “The Origins of the Grape Program at foundation Plant Materials Service”, p. 222, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000.

The most well-known grape importer of the era was a Hungarian immigrant named Col. Agostín Haraszthy, a vineyard owner at the Buena Vista Ranch in Sonoma. He stimulated interest in grape growing and winemaking in the state and campaigned to upgrade the varieties planted in California. In 1861, he was appointed by Governor J.G. Downey as a “commissioner” to study ways to improve the grapevine culture in California. Haraszthy ultimately received state “sponsorship” (but not financing) for his 1861 trip Europe, where he reportedly acquired about 300 mostly Vitis vinifera grape varieties for import to California. 27 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine, p. 147 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998).

Although Haraszthy has been credited by some with the initial importation of Zinfandel into California, there is persuasive evidence against that theory (see chapter of this book entitled The Origin of California’s Zinfandel). The extent of the distribution of the Haraszthy grape collection throughout the state is not known nor was the collection well documented or well preserved. 28 Sullivan, Charles L., Zinfandel, A History of a Grape and its Wine, pp. 56-57 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, 2003); Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 279-282 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Charles Wetmore, First Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer, 1881, Appendix I, p. 184.

The work of these and other early pioneers resulted in a substantial increase in the number of vines planted in northern California in the 1850’s and laid the groundwork for the wine industry that came to exist in California by the mid-20th century. 29 Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 16, 22 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951). Records from the California State Register for 1859 showed a total of 5,883,845 vines planted in the state. Plantings had more than doubled between 1856 and 1858. In 1862, there were 8,000,000 vines. Another increase would occur in 1869 after the railroad arrived.

Despite the acreage and production increases, there was a need for formal research in the viticulture and enology disciplines. Pinney characterized the industry in 1860 as “young and untaught”. 30 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, p. 267 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989) He pointed to a lack of knowledge regarding soil and appropriate grape varieties and commented that “most [growers] never had seen a vineyard” prior to planting. He referred to poor quality wine that was “too alcoholic and lacked character”. 31 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 267-268 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989)

Vincent P. Carosso wrote about the formative years in the California wine industry: “despite the increased plantings within the state, large vintages were the exception and commercial viniculture in the 1850’s was still primitive and conducted on a small scale”. 32 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 262 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years 1830-1895, pp. 16, 22 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1951). The Committee on Wines of the State Agricultural Society stated in 1860: “most of our people have never seen a vineyard. Whoever will enlighten [them] on the most approved modes of culture and …the scientific and practical treatment of the grape juice in the making of wine will be a great public benefactor”. 33 Transactions of the California State Agricultural Society, 1860, p. 244 (Sacramento 1861), as cited in Pinney, supra, vol. 1, at p. 267.

Influential viticulturists and nurserymen were eager to diversify California cultivars beyond the Mission grape and the few Vitis vinifera cultivars present in the state. Serious efforts to expand the number and quality of European wine grape cultivars were begun between 1860 and 1880. 34 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 347 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989) Plant material was shared and exchanged freely up and down the state, especially during the wine boom of the late 19th century when many new varieties were imported from Europe and elsewhere.

University viticulture work begins

In 1864, the State of California exercised a right acquired with statehood and formally accepted college lands guaranteed in the federal Morrill Land Grant College Act (1862). The state constitution (1849) included a commitment to create a state university, resulting in the Agricultural, Mining and Mechanical Arts College in 1866. 35 Maynard A. Amerine, Professor Emeritus of Enology, FOREWORD, University of California, Davis, Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings (1880-1980), p. III (Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, January 1982).The Legislature approved the merger of the Agricultural College with the private College of California in 1868, resulting in the University of California (U.C.). As a “land grant college”, UC was eligible to receive federal land and direct research grants in exchange for offering instruction in agricultural and mechanical arts. As a result of the 1868 merger, the University was authorized to offer courses in letters and pure sciences as well as the “practical courses”. 36 Verne A. Stadtman, The University of California 1868-1968, A Centennial Publication of the University of California, McGraw-Hill Book Company, San Francisco and New York (1970): 21-22, 27, 32-33. Scheuring, Ann Foley, “Growing a World Class Institution”, California Agriculture, July-August 1993, p. 27.

The new University of California received its first 40 students in 1869 at a campus in Oakland. Classes began on the Berkeley campus in 1873. Twelve young men known as the “12 Apostles” were the first to receive U.C. diplomas in 1873; one of the twelve was Charles Wetmore, who would later be a key figure in the California grape and wine industry.

In order to preserve rights to the land granted by the Morrill Land Grant Act, the U.C. enabling legislation provided special considerations for the agricultural curriculum, including a promise that a College of Agriculture would be the first college to be established at the University. The first building at Berkeley was assigned to the new College of Agriculture in 1870. 37 Maynard A. Amerine, “Chemists and California Wine Industry”, Am. J. Enol.Vitic, 10: 124-125 (1959), originally presented at Symposium on History of Chemistry in California, 133rd Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, April 1958.

Experimental work in viticulture and wine making was begun as a special discipline at the University in 1868 in facilities located on the Berkeley campus. 38 E.W. Hilgard, Report on the Agricultural Experiment Stations of the University of California, with descriptions of the regions represented, being part of the combined reports for 1888-1889 (Sacramento, 1890). The northwest sector of the campus was developed for agricultural use beginning in 1874. Many horticultural crops were planted at Berkeley, including 73 grapevine varieties in 1874-1875. University reports on the vineyard do not indicate the source material for the 73 vines. 39 Verne A. Stadtman, The University of California 1868-1968, A Centennial Publication of the University of California, pp. 141-143 (McGraw-Hill Book Company, San Francisco and New York, 1970).

Eugene W. Hilgard

One of the most productive research scientists at Berkeley in the early decades was Eugene W. Hilgard, who succeeded Ezra Carr as Professor of Agriculture at the University of California in the winter of 1874-1875. 40 Verne A. Stadtman, The University of California 1868-1968, A Centennial Publication of the University of California, p. 60 (McGraw-Hill Book Company, San Francisco and New York, 1970). Hilgard shaped the University viticulture and enology work in those early days, assisted by Frederic Bioletti. Hilgard’s effort was remarkable in light of the fact that he had no prior formal training in either grape growing or wine making prior to coming to California in 1874. The story of the creation of the UC viticulture and enology program with an analysis of Hilgard’s accomplishments is comprehensively told by former UC Enology Professor Maynard A. Amerine in a 1962 volume of the journal Hilgardia. 41 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia 33:1 (July 1962), a Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, University of California, Berkeley; see also, Stadtman: Ch 10, “Eugene Hilgard Rescues the College of Agriculture” supra, at pp. 141-154. That volume also concludes with a bibliography of Hilgard’s published works on viticulture.Hilgard was born in Germany but moved to the United States as a child in 1835. His formal education and professional expertise were in geology, chemistry, and soil science. He was a respected soil scientist and held professorships in agricultural chemistry and geology/natural history at the University of Mississippi and University of Michigan, respectively. Hilgard and his father had experimented with growing grapevines.

Hilgard’s professional involvement with viticulture began when he assumed the position of Professor of Agriculture at UC Berkeley in 1874. It is speculated that his interest in viticulture and wine-making was stimulated in 1878 when he was a member of the group selected to judge wines at the 13th Mechanics Institute Fair in San Francisco where California wines were exhibited and formally evaluated for the first time. 42 Professor E.W. Hilgard, College of Agriculture, Supplement to the Biennial Report of the Board of Regents for 1878-79, pp. 61-64 (University of California, Sacramento, 1879); Professor E.W. Hilgard, Report to the President of the University, from the Colleges of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts, p. 15 (University of California, Sacramento 1877). Reference to viticultural work dominated Hilgard’s Second Report to the Board of Regents a year later (1879) as Professor of Agriculture at Berkeley.

Hilgard and the University were challenged by several serious issues besetting the grape and wine industry in the late 1870’s. There had been an over-expansion of grape plantings between 1870 and 1874 as 35 of the 44 counties of the state planted vines on a large scale. In 1873 there were approximately 30 million vines planted in California; by 1876, there were 43 million vines. A worldwide depression appeared in 1875-1876 just as the new vines came in to bearing. Much of the wine produced in California was poor due ignorance or inexperience regarding production practices. 43 Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, a Study of the Formative Years (1830-1895), pp. 76-115 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1951).

Notwithstanding the significant grape importations to California in the 1850’s and 1860’s, important varieties such as the black grapes of Bordeaux, the white Sauternes and Spanish sherry varieties, were present in the state in experimental lots only until viticulturists made more aggressive efforts in later decades to increase the plantings. The wine grape industry in 1880 was still dominated by two varieties – Mission and Zinfandel. Most felt that Mission produced a coarse and inferior wine.

Finally, the root louse phylloxera was identified in Sonoma County in 1873. By 1876, the increased virulence of the disease threatened the grape and wine industry.

44 Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, a Study of the Formative Years (1830-1895), pp. 76-115 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1951);

Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 343 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989).

Arpad Haraszthy, President of the Board of the State Viticultural Commissioners, recalled the crisis when he wrote there was a “woeful lack of knowledge, a want of system, no beaten paths to follow and but a few acknowledged authorities to apply to for information [on vine planting]….and the desire for the formation of some State institution, where such practical knowledge might be obtained as was necessary to the successful conduction of this important branch of agriculture”. 45 Arpad Haraszthy, President, Annual Report of California Board of State Viticultural Commissioners for 1887, pp. 7-9 (State Printing Office, Sacramento, 1888). It was in this context that grape growers, winemakers and scientists intensified efforts in the California Legislature in 1879 to establish a state body to assist the wine industry.

The Division of Viticulture at UC

Hilgard lobbied the Legislature for a $10,000 appropriation for systematic and scientific studies on wine at the University and for funding to establish an experiment station system within the university “to resolve practical questions”. In a letter to Senator S.C. Nye in April of 1880, Hilgard indicated support for the bill then pending and concluded: “…the growers need to know….which of the 2,500 grape varieties they shall choose ….[for improvement of California’s wines].” 46 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33, no. 1, (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962). Amerine points to that comment as the beginning and the heart of Hilgard’s viticultural work.The Legislature passed a law on April 15, 1880 that did two things: (1) created the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners to promote the viticultural industries of the state; and (2) delegated certain duties related to instruction and research in viticulture to the University of California. The legislation authorized the University of California’s Department of Viticulture and Viticulture Experiment Station system. 47 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 342, 350 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Hilgard, Report of the Viticultural work during the seasons 1883-84 and 1884-85, being Appendix IV to the Report for the year 1884; with notes regarding the vintage of 1885-86 (Sacramento, 1886a). The act provided $3,000 to the University for the work and authorized the University to accept donations of land for experimental vineyards. The Board of Viticultural Commissioners was given $4,000.

The Division of Viticulture (later Department of Viticulture & Enology) was established at U. C. Berkeley in 1880. Although some minor experimental work had been conducted on the campus since 1878, systematic research in viticulture and wine making was begun in 1880 with a laboratory and cellar for fermentation located on the Berkeley campus. 48 E.W. Hilgard, Report on the Agricultural Experiment Stations of the University of California, with descriptions of the regions represented, being part of the combined reports for 1888-1889 (Sacramento, 1890). The cellar was completed in October, 1880, near South Hall and 14 experimental fermentations were completed that year.

The first scientific studies on wine in California were made at the University of California under Professor Hilgard in the period 1880 to 1900. 49 Maynard A. Amerine, “Chemists and California Wine Industry”, Am. J. Enol.Vitic, 10: 126 (1959), originally presented at Symposium on History of Chemistry in California, 133rd Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, April 1958. Approximately 20 chemists were engaged in grape and wine research at the University between 1880 and 1895. The grapes were crushed at Berkeley, musts were analyzed, fermented and wines tasted and analyzed by scientists, chemists and tasters. Hundreds of small fermentations, analyses and tastings ensued.

Hilgard’s primary viticultural mission was to improve the quality of grapes and wines suitable for California. His work plan was based on language in section 8 of the enabling legislation. He formulated an ambitious work plan for the new Division of Viticulture to make a “selection of proper varieties that were best calculated to bring the pure wines of California into use as table wines, instead of numerous artificial compounds [then] dispensed as table clarets under French labels”. 50 Eugene W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in Charge to the Board of Regents, 1880, Appendix 8 for Viticulture Work, pp. 85-88 (published in 1881).

Hilgard described his plan in regular reports to the Regents: “the establishment of more definite qualities and brands of California wines, resulting from a definite knowledge of the qualities of each of the prominent grape varieties and their influence upon the kind and quality of wine”. The information included treatment required by each variety in the cellar during fermentation and blending; and the differences caused by difference of location, climate, etc., as well as by different treatment of the wines themselves. 51 Eugene W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in Charge to the Board of Regents, 1880, Appendix 8 for Viticulture Work, pp. 85-88 (published in 1881).

The Central [Experiment] Station was also established at Berkeley in response to authorization in the 1880 legislation for a viticulture experiment station. 52 Hilgard, Report of the Viticultural work during the seasons 1883-84 and 1884-85, being Appendix IV to the Report for the year 1884; with notes regarding the vintage of 1885-86 (Sacramento, 1886a). Hilgard believed that the Berkeley campus was unsuitable for grapevines due to its climate and the presence of phylloxera. This feeling provided impetus for the later establishment of experiment stations in other locations as well as the University Farm in Davis. Creation of additional outlying stations for the University was delayed for many years by lack of funds.

UC versus the Board of State Viticulture Commissioners

The Board of State Viticultural Commissioners (Board) was also authorized by act of the Legislature on April 13, 1880. On March 4, 1881, the legislature gave the Board quarantine duties directed at control of phylloxera. 53 Maynard A. Amerine, “Chemists and California Wine Industry”, Am. J. Enol.Vitic, 10: 126 (1959), originally presented at Symposium on History of Chemistry in California, 133rd Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, April 1958.Although the Legislature intended that the 1880 act result in cooperation between the Board and the University, the result was an extended period of acrimony between the two over substantive matters and the division of the money allocated jointly to the two entities. E.J. Wickson, Dean of the College of Agriculture, wrote in 1917: the 1880 act “resulted, during the first year following, in fermentation among the cooperators fiercer than in the materials they were authorized to investigate”. 54 Report of the College of Agriculture and the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California, from July 1, 1917 to June 30, 1918, page 78 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1918). The rivalry over money peaked over an 1885 allocation but was eventually compromised. Nonetheless, ill feeling prevailed for more than a decade.

The University-Board relationship was acrimonious on multiple topics, including techniques for the proper evaluation of wines. 55 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 343-347 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 9-12 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962). Hilgard’s protocol for wine evaluation called for making wine in small (7 gallon) test batches in the Berkeley lab. The results of chemical analyses of the grape juice and wine were reported extensively in University reports between 1880 and 1896.

Board Commissioner Charles Wetmore did not believe that the small lots (as opposed to commercial quantities) could produce representative results. He never visited the University lab. The Board had nine Commissioners, including influential wine growers from around the state such as Charles Wetmore, Charles Krug, Arpad Haraszthy, Isaac De Turk, George West, L.J. Rose and J. De Barth Shorb. Some members of the Board prided themselves on being “practical” and using common sense in wine making and dismissed chemical analysis as a valid evaluative tool. 56 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 351 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989); Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 9-10 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962).

Wine samples from the University and the Board were submitted to the Third Annual Viticultural Convention in December, 1884, and the tasting committee was very impressed with the University samples; a committee later chosen to investigate the University lab supported a resolution to the Legislature to provide $10,000 to the University to expand the lab. 57 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 9-10 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962); Hilgard, Report of the Viticultural work during the seasons 1883-84 and 1884-85, being Appendix IV to the Report for the year 1884; with notes regarding the vintage of 1885-86, page 13 (Sacramento, 1886a). The subsequent 1885 appropriation was given jointly to the University and Board but was eventually evenly split in 1886 after Wetmore insisted on joint control over the lab. Other issues such as the use of yeast cultures and amount of alcohol in table wines proved contentious.

A Chief Executive Officer position was created for the Board in 1881. The first CEO of the Board was Charles Wetmore. Wetmore, a journalist, real estate developer and wine grower, dominated and directed the Board’s activities for the first ten years in various capacities as a Commissioner, President and Chief Executive Officer. He was a controversial and intense man. Hilgard held strong opinions on temperance and was a moderate drinker; he may have held strong feelings on Wetmore’s “predilection for spirits”. 58 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 14 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962)

The battle between the Board and University was conducted largely through Hilgard and CEO Wetmore. Letters, public statements, and newspaper articles aired the continuing acrimony between the two men until as late as 1904. The jealousies and disputes over funding persisted until the Board was dissolved.

The Board of State Viticulture Commissioners made some valuable contributions to the California industry, most noticeably in the area of increasing awareness and plantings of better grape varieties in the state. 80% of the 35,000 acres of grapes planted in California prior to 1880 was to the Spanish cultivar Mission. By 1888, 90% of the 150,000 acres of vines in the state consisted of other “foreign” varieties. Wine writer and business/economics historian Vincent Carosso credited the Board with plantings of more vines of better grade winegrapes and with causing the importation of more and better varieties. 59 Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, A Study of the Formative Years (1830-1895), pp. 123-124 (University of California Press, 1951).

In 1884 Wetmore wrote a report on the state of California’s vineyards and the varieties known to be in the state at the time. In his Ampelography, Wetmore lamented the lack of systematic planting in the state of varieties necessary to reproduce quality European wines and encouraged the import of those European grapes to improve California viticulture. 60 Wetmore C.A. Part V. Ampelography. Second Annual Report of the Chief Executive Viticultural Officer to the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the Years 1882-1884, pp. 103-151 (1884); Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, p. 210, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000 He specifically referenced the noblest French and Spanish varieties and white Sauternes. Wetmore and other Commissioners travelled to Europe and imported European varieties for their own vineyards in California. 61 Charles Wetmore, Classification of California Wines, First Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer, pp. 65-66 (1881).

Historian James T. Lapsley reported that the late 1880’s saw a frenzy of planting of Bordeaux varieties in California, largely in response to the phylloxera epidemic in Europe. California growers were planting Bordeaux varieties such as Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec, Cabernet franc and Petit Verdot, Semillon and Petit Syrah. 62 James T, Lapsley, Bottled Poetry, Napa Winemaking from Prohibition to the Modern Era, pp. 40-46 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1996); Charles L. Sullivan, Napa Wine, A History from Mission Days to Present, 2nd ed., p. 136 (The Wine Appreciation Guild, San Francisco, 2008); Lynn Alley and Deborah Golino, “The Origins of the Grape Program at foundation Plant Materials Service”, p. 222, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. California had a total of 166,952 acres by 1891, which included 60 grape varieties. 63 M. Andrew Walker, UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials, p. 211, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000.

Most authorities concluded that both the Board of Viticultural Commissioners and the University made positive contributions to the California grape and wine industry. 64 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, pp. 343-350 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989). The University proceeded with scientific analyses while the Board was commercially oriented and “practical”. Despite the conflict, both improved the quality and reputation of the California grape and wine industry.

When the State Legislature repealed the authority of the State Board of Viticultural Commissioners on March 27, 1895, the Board’s functions, library of technical literature and records were transferred to the U.C. College of Agriculture. That exacerbated the animosity felt by growers and wine men toward the University and many felt that Hilgard was a “viticultural fraud”. 65 Vincent P. Carosso, The California Wine Industry, a Study of the Formative Years (1830-1895), p. 142 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1951). The University was thereafter exclusively entrusted with viticulture research in California. Maynard Amerine concluded that the Legislature’s action was a validation of Hilgard’s methods and statement that “it is the quality of the wine which counts”. 66 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 12 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962)

The Heart of Hilgard’s Work

From 1880 to 1896, Hilgard devoted a considerable portion of his time to research efforts to improve California wine through the use of appropriate wine grape varieties best suited to specific regions of the state. 67 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, p. 211, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. Frederic Bioletti was hired in the latter stages to assist in the research. The work of those men foreshadowed the later work at U.C. Davis in the mid-20th century culminating in the “Winkler zone” approach to planting grape varieties. The climate region analysis was the product of a long history of University research that evaluated grapes and wines in the coastal regions of California – from 1882 to 1958 – in both University vineyards and private grower test plots.The work by Hilgard and his associates at Berkeley focused attention on the fact that the state was composed of unique climatic regions that acommodated different wine grape varieties. 68 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 8-9 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962). Hilgard explained that his mission had been to select proper varieties for California that were “best calculated to bring the pure wines of California into use as table wines, instead of numerous artificial compounds now dispensed as ‘table clarets’ under French labels”. 69 Eugene W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in Charge to the Board of Regents, 1880, Appendix 8 for Viticulture Work, pp. 85-88 (published in 1881). He stated in a report to the Regents in 1879 that the “growers need to know, and that quickly, which of the 2,500 grape varieties they should choose”. 70 Hilgard, E.W., Report of the Professor of Agriculture to the President of the University, as part of the 2nd Report to the Regents in 1879, p. 113 (State Printing Office, Sacramento, 1879).

Hilgard wrote: “The result of our laboratory work has been to establish a definite basis for rational wine making in this State by determining both the cultural and wine-making qualities of all the more important grape varieties in the several regions where our [experiment] stations were or are now located….representing the largest and most complete systematic investigation of the kind on record thus far in any country”. 71 E.W. Hilgard, Partial Report of the Work of the Agricultural Experiment Stations of the University of California for the years 1895-1896; 1896-97 [18th Report], p. 14 (1898).

Amerine characterized the above-stated mission as the heart of Hilgard’s work on grapes and wine. 72 Maynard A. Amerine, Professor Emeritus of Enology, FOREWORD, University of California, Davis, Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings (1880-1980), p. III (Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, January 1982).

The University’s viticulture research under Hilgard was summarized in two major reports to the Regents in the 1890’s. A detailed and lengthy report on the evaluation of primarily red wine grapes was prepared by Louis Paparelli under Hilgard’s direction and published in 1892. 73 L. Paparelli, under the direction of E.W. Hilgard, Report of the Viticultural Work during the Seasons 1887-89 with Data Regarding the Vintage of 1890, Part I. Red Wine Grapes, being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University [13th Report], Sacramento, 1892. Cited hereafter as 13th Report (1892) The final report (a continuation of the 1892 report) on the viticultural work was prepared by Frederic Bioletti and published in 1896 and included a summary of work on both red and white grapes. 74 F.T. Bioletti, Report of the Viticultural Work During the Seasons 1887-93 with Data Regarding the Vintages of 1884-1895, Part I. Red Wine Grapes (continued from Report of 1892) and White Wine Grapes, being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University [17th Report], Sacramento, 1896. Cited hereafter as 17th Report (1896) Those two reports documented much of the experimental work which had been accomplished the previous 13 years.

Hilgard wrote or directed a series of reports from 1880 through 1896 that described the grape varieties received each year, a clear viticultural summary and source for each variety, ampelographical notations, and expectations for the variety under various conditions and locations. Published reports of the University on viticulture and enology equaled all those printed on other agricultural topics during the period 1880 to 1918. 75 Maynard A. Amerine, “Chemists and California Wine Industry”, Am. J. Enol.Vitic, 10: 125 (1959), originally presented at Symposium on History of Chemistry in California, 133rd Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, April 1958. The annual report of the U.C. College of Agriculture for 1917-1918 gave a history of agricultural research at the University starting in 1877, including a list of all publications on grapes and wines to 1917. 76 Maynard A. Amerine, “Chemists and California Wine Industry”, Am. J. Enol.Vitic, 10: 124-125 (1959), originally presented at Symposium on History of Chemistry in California, 133rd Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, April 1958. The list was included as part of the Director of the Experiment Station Report to the President, at page 102 in the document.

In addition to the formal reports to the Regents regarding viticultural work, the University began issuing bulletins in 1884, the majority of which were authored by Hilgard between 1884 and 1890. Bulletins were developed because the formal University reports were not distributed regularly or widely to California members of the grape and wine industry. Hilgard explained in his Report for 1883-1884 that the issuance of “short bulletins” of completed work at brief intervals (one to three weeks) was implemented to render University work more useful and generally known to the agricultural population. The bulletins gave advice on issues such as phylloxera, vineyard soil preparation and maintenance, fertilizers, grape varieties, rootstocks, and grafting. Bulletins were mailed to the newspapers of the state for publication in their regions and to agricultural colleges and experiment stations throughout the United States. A complete list of the bulletins from 1884 through 1917 is included in the Annual Report of the Experiment Station Director for 1917-1918. 77 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 18 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962); Report of the College of Agriculture and Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California, July 1, 1917, to June 30, 1918, p. 103 (Sacramento, 1918). Twenty-eight University reports or bulletins pertained to grape products and 46 to wines.

The value of the early viticulture work at the University has been subject to some debate. Amerine and others have described what they saw as significant contributions Hilgard made to California viticulture and wine-making.

Amerine conceded that Hilgard did not finalize his recommendations as was the standard in later years. Nevertheless, Amerine assessed Hilgard’s important contributions to the industry as knowledge on the relation of climate to grape composition and emphasis on the scientific nature of wine-making and preventing adulteration of wine with other products. Hilgard insisted on quality, in winemaking and grape selection and growing. He and Bioletti were the first to research and report on the response of many California grape varieties to the unique climatic characteristics throughout the state. 78 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 16-17 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962); Maynard A. Amerine, “Chemists and California Wine Industry”, Am. J. Enol.Vitic, 10: 124-125 (1959), originally presented at Symposium on History of Chemistry in California, 133rd Meeting of the American Chemical Society, San Francisco, April 1958.

Thomas Pinney concluded that Hilgard’s experiments produced an impressive body of objective information on wine qualities. 79 Thomas Pinney, A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, vol 1, p. 351 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989). U.C. Davis’ Amerine referred to the systematization of viticultural knowledge in California and noted the carefully recorded performance measures for each variety from the crush onwards. 80 Maynard A. Amerine, “Hilgard and California Viticulture”, Hilgardia, A Journal of Agricultural Science published by the California Agricultural Experiment Station, vol. 33(1): 16-17 (University of California, Berkeley, June 1962)

Leon Adams pointed to Hilgard’s recommendation on “early harvest” based on acid and sugar balance rather than the European procedure of leaving grapes on the vine too long. That advice and low temperature fermentation would not be followed by growers and wineries until the 1960’s. Adams also cited the study of interaction of climate and varietal selection and the careful records of the performance of each cultivar in the formation of the wine. 81 Leon Adams, WINES OF AMERICA, pp 226-227 (4th ed., 1990).

U.C. Experiment Station system

Another lasting contribution to the grape and wine industry from the early viticulture work came from the vineyards of the University Experiment Station system. Hilgard became Director of the U.C. Agricultural Experiment Station and oversaw the work on grape varietal comparisons in the different climates and locations around the state. Many of the grape accessions established in those vineyards in the late 19th century have continued as heritage selections in the foundation grapevine collection at Foundation Plant Services at UC Davis.Hilgard introduced the subject of an “experimental farm” in the Report to the U.C. Regents in 1877. He distinguished that concept from a “model farm” (such as that later established in Davis in 1908) by stating that an experimental farm served the purpose of investigation with a view to acquiring new facts in the theory or practice of agriculture for the guidance of local farmers. He stated that a system of “local experiment stations [in the four or five distinct climatic divisions of the state] will be the center from which rational and correct practice will radiate in all directions”. 82 Professor E.W. Hilgard, Appendix A to Report to the President of the University from the College of Agriculture and the Mechanical Arts for 1876-77 [First Report], pp. 7-8, 13-15 (Sacramento, 1877); Professor E.W. Hilgard, College of Agriculture, Supplement to the Biennial Report of the Board of Regents for 1878-79 [2nd Report] p. 9 (Sacramento, 1879). Hilgard argued that such a system would facilitate “small culture experiments” to evaluate particular regions where wine grape cultivars were suitable and adaptable.

The University began the evaluation of grape varieties in 1878 despite the lack of funding for University stations. Hilgard intensified lobbying efforts with the UC Regents in 1879 for funding to establish an experiment station system within the University “to resolve practical questions”. 83 Professor E.W. Hilgard, College of Agriculture, Supplement to the Biennial Report of the Board of Regents for 1878-79 [2nd Report] p. 9 (Sacramento, 1879).

A U.C. Viticulture Experiment Station was authorized by the California Legislature in 1880 in the same act that created the State Viticultural Commission. The Central Station (including cellar and laboratory) was established at Berkeley in that year. However, creation of additional stations within the University was delayed for many more years by lack of funds.

The lack of funding in the early 1880’s forced Hilgard to arrange for privately-funded sources of grapes and wine to assist with University viticulture work. Wine producers throughout the state cooperated in the studies beginning in 1880 by sending shipments of grapes and wines from private vineyards to the University for analysis. Donated samples used in University research included Hilgard’s own vineyard at Mission San Jose, H.W. Crabb and Charles Krug in Napa, John Drummond and Jacob Gundlach in Sonoma, Charles Lefranc and others in Santa Clara, Charles Wetmore in Livermore, George West in Stockton, and Professor Eisen in Fresno. The Natoma Water and Mining Co. in Folsom imported 40 cultivars from Europe and planted them in 1883. Natoma donated sample lots of wines of 40 cultivars to the University lab for analysis in 1894 and 1895. 84 E.W. Hilgard, Report of the viticultural work during the seasons 1885 and 1886, being Appendix VI to the report for the year 1886 [7th Report], p. 67 (1886b); E.W. Hilgard, Report of the viticultural work during the seasons 1883-84 and 1884-85, being Appendix IV to the Report for the year 1884 [6th Report, includes time 1882-1886], pp. 54-83 (1886a); E.W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in Charge to the President, being a part of the Report of the Regents of the University, also called Biennial Report for 1883 and 1884 [5th Report], pp. 9, 13 (1884); Eugene W. Hilgard, Report of the Professor in Charge to the Board of Regents, 1880, Appendix 8 for Viticulture Work, pp. 85-88 (published in 1881). In later years, grapes from the University experiment stations located throughout the state were used in the evaluations.

In 1883-1884, a close associate of Hilgard’s named John T. Doyle assigned his own property to the University for use as an experiment station vineyard. Doyle was a noted trial lawyer, scholar and important leader in the California wine industry in the 19th century. In the 1880’s, he purchased land near what later became Cupertino on the Peninsula in the San Francisco Bay Area and founded a winery. The two-year old vines on his property consisted of forty varieties imported from Europe and collected from around the state. That privately-funded station became known as the West Side Santa Clara Valley Station in Cupertino. 85 Sullivan, Charles L., A Companion to California Wine, p. 91 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998); E.W. Hilgard, Report of the viticultural work during the seasons 1885 and 1886, being Appendix VI to the report for the year 1886 [7th Report], p. 124 (1886b); E.W. Hilgard, Report of the viticultural work during the seasons 1883-84 and 1884-85, being Appendix IV to the Report for the year 1884 [6th Report, includes time 1882-1886], p. 160 (1886a).

Hilgard’s vision for a complete University experiment station system was realized in 1888. The final piece of the puzzle was put into place that year when Hatch Act (1887) funding for land grant colleges was provided to fund outlying general culture stations under the auspices of the University for the purpose of conducting extension work. 86 Anne Foley Scheuring, Science & Service, A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, p. 40 (ANR Publications, University of California, Oakland, 1995). The Act of 1887 Established Agricultural Experiment Stations, 24 U.S. Statutes at Large 440, section 2. E.W. Hilgard, Report of Work of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California for the year 1890 [12th Report] (1891).

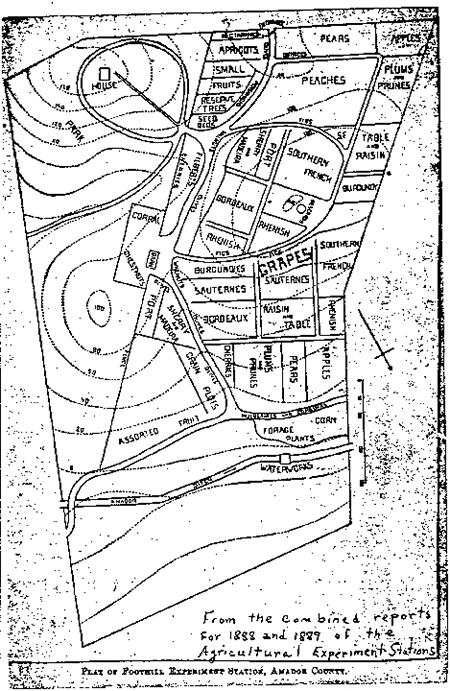

Five general culture stations were eventually established. The Central Station at Berkeley (“the Central Experiment Station”) was established first in 1880. Four other general culture stations were created in Chino Valley (South California Station in Pomona), Paso Robles (The South Coast Station in San Luis Obispo County), Tulare (San Joaquin Valley Station) and the Sierra Foothill Station in Jackson, Amador County. Two other stations under private auspices were developed in 1883 at Cupertino (West Side Santa Clara Valley Station) and Mission San José (East Side Santa Clara Valley Station). 87 E.W. Hilgard, Report of Work of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California for the year 1890 [12th Report] (1891); F.T. Bioletti, Report of the Viticultural Work During the Seasons 1887-93 with Data Regarding the Vintages of 1884-1895, Part I. Red Wine Grapes (continued from Report of 1892) and White Wine Grapes, being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University [17th Report], Sacramento, 1896; L. Paparelli, under the direction of E.W. Hilgard, Report of the Viticultural Work during the Seasons 1887-89 with Data Regarding the Vintage of 1890, Part I. Red Wine Grapes, being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University [13th Report], Sacramento, 1892.

Grapes were grown for evaluation in the local conditions of each of the five general culture stations in the system, as well as the private viticultural stations. 88 E.W. Hilgard, Report of Work of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California for the year 1890 [12th Report], p. 197 (1891). The early work performed at the stations did not include clonal selection or improvement. The Experiment Station system was tasked with determining suitable grape varieties to be grown in the various locations, climates and regions throughout the state.

The vineyards at the Sierra Foothill Experiment Station have special significance to the FPS foundation grapevine collection. The Foothill Station was established in 1889 4 ½ miles northeast of Jackson in Amador County. The Foothill Station and Paso Robles Station were “abandoned” by the University of California in 1903 for financial reasons. The vineyards at the Jackson station were not removed. U.C. Davis Plant Pathology scientist Austin Goheen “rediscovered” the old overgrown vineyards in 1963 and later obtained a map of the 1889-1892 plantings from the archives of the University of California library at Berkeley. He was able to collect 25 accessions from the old vines at the Jackson station and incorporate them into the FPS foundation grapevine collection, where they remain today. The complete story of Goheen’s rediscovery of the vineyard is contained in the 2006 FPS Grape Program Newsletter. 89 Dr, Austin Goheen, emeritus USD, ARS Plant Pathologist, “Jackson Vineyard Story”, p. 24, FPS Grape Program Newsletter, Foundation Plant Services, November 2006.

The grape collections at each of the five general culture stations and three private viticultural stations were used in the University’s evaluation of appropriate grape varieties for California. The grape varieties from those stations eventually supplied the new University vineyard at the University Farm in Davis in 1908. The Department of Viticulture “Variety collection” at Davis was the source of many of the selections that still exist in the FPS foundation collection. 90 E.W. Hilgard, Report of Work of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California for the year 1890 [12th Report], p. 197 (1891).

As mentioned above, an extensive body of published material exists describing the early work of the University of California Department of Agricultural Experiment Station, including reports, circulars and bulletins written by Hilgard and others in the College and published by the University between 1877 and 1918. 91 Annual Report of the Director, Report of the College of Agriculture and the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California, from July 1, 1917, to June 30, 1918, page 102 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1918). The intent was to publish annually, but adequate funding to perform the work was a constant problem in those early years, as was funding to support production of regular reports. Hilgard’s reports to the President of the University and to the Regents between 1880 and 1896 described the early viticulture and wine-making work, the ongoing struggle for funding, and development of the University experiment station system. Hilgard’s successor Edward J. Wickson was busy with college expansion activity and submitted no formal reports as Dean of the College of Agriculture from 1905 to 1912 which broke a series that documented the history of the College from 1877 through 1940. 92 Ann Foley Scheuring, Science & Service, A History of the Land-Grants University and Agriculture in California, page 62 (ANR Publications, University of California, Oakland, 1995).

Eugene Hilgard retired and became an Emeritus Professor in 1906. He died in 1916 at the age of eighty-three. Frederic T. Bioletti had assumed the major responsibility for the U.C. viticultural and enological work around 1900 but then left for a teaching position in South Africa. He returned several years later and became “the great influence” on that work in the University between Hilgard’s retirement and the post-Repeal era beginning in 1933. 93 Maynard A. Amerine, Professor Emeritus of Enology, FOREWORD, University of California, Davis, Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings (1880-1980), p. III (Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, January 1982).

Frederic T. Bioletti

Frederic T. Bioletti was an enologist and “life-long botanist”. He was born in Liverpool, England, in 1865. Bioletti’s widowed mother married Captain John H. Drummond, a California grape and wine pioneer who developed the respected vineyard known as Dunfillan in Glen Ellen, Sonoma County, in the 1870’s and 1880’s.

Bioletti received his early viticulture and enology training at Stanford’s Viña Ranch as well as at other wineries in Sonoma and Napa in the 1880’s. He attended the University of California beginning in 1886, where he studied and worked with Professor Hilgard. 94 Ernest Peninou, History of the Sonoma Viticultural District, volume 1, p. 105 (San Francisco, California, 1998).

After his graduation, Bioletti began a career as foreman of the University Cellar at Berkeley in 1889. He assisted Hilgard with the preparation of reports on the evaluation of grapes and wines from the U.C. Experiment Stations. Bioletti became the University’s first Professor of Viticulture in 1898. 95 Maynard A. Amerine, Professor Emeritus of Enology, FOREWORD, University of California, Davis, Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings (1880-1980), p. IV (Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, January 1982).

In 1901, Bioletti left for South Africa where he taught at a university for three years. After some international travel and work in California vineyards, he returned to the University of California between 1907 and 1909. Bioletti became head of the Division of Viticulture at the University in 1912. 96 From an image in Wines & Vines magazine, August 1935, shown on page 125 of: A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Interviews conducted by Ruth Teiser and Joann Leach Larkey, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1973. E.W. Hilgard, Letter of Transmittal, Report of Work of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California, from June 30, 1901, to June 30, 1903, p. 14, being part of the Report of the Regents of the University (Sacramento, 1903)

Maynard Amerine characterized Bioletti’s “knowledge of viticulture [as] encyclopaedic”. 97 Maynard A. Amerine, Professor Emeritus of Enology, FOREWORD, University of California, Davis, Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings (1880-1980), p. IV (Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, January 1982). Albert Winkler was Bioletti’s successor as Chair of the Department of Viticulture (1935) and assessed that Bioletti was “a very capable individual, one of the best editors [of publications] that the agricultural college ever had”. 98 A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, pp. 70-71, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Interviews conducted by Ruth Teiser and Joann Leach Larkey, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1973. Winkler believed that Bioletti had not received the recognition he deserved because he did not get along well with the industry.

Some of the publications with which Bioletti was involved defined the U.C. recommendations on the suitable grapes for planting around the state.

After twenty years of observation and evaluation by scientists in the University Experiment Station system, U.C. in 1907 issued a recommended list of grape varieties appropriate for planting in the various regions of California.

Bioletti’s 1907 Experiment Station Bulletin was entitled “The Best Wine Grapes for California” (Bulletin no. 193). 99 Lynn Alley and Deborah A. Golino, “The Origins of the Grape Program at Foundation Plant Materials Service”, pp. 222-223, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. He was the first to divide California into viticultural districts by their climates: coastal counties for table wines and interior valleys for dessert wines. 100 Leon Adams, Wines of America, p. 228 (4th ed., 1990). Bioletti proposed an early version of the regional approach that later become known as the “Winkler climate regions”, based on an 1883 study done in France. 101 Walker, M. Andrew. 2000. “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, p. 211, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000. He also observed that the finest wines produced in California in 1907 were the product of Cabernet Sauvignon but noted that growers consistently rejected the variety almost everywhere due to low yields. 102 F.T. Bioletti, “The Best Wine Grapes for California – Pruning Young Vines – Pruning the Sultanina”, page 142, Bulletin No. 193, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station (Berkeley, November 1907). Shields Library SB 189.5, C3, C 251.

Twenty years later Bioletti produced a publication in 1929 (revised 1934) on “The Elements of Grape Growing in California”, in which he included a section describing the grape varieties then being grown in California. The 1929 Extension Circular reviewed the merits of California red and white wine grapes. 103 Frederic T. Bioletti, Elements of Grape Growing in California, pp. 26, 34, Circular 30, California Agricultural Extension Service, University of California (Berkeley, March, 1929 – Revised April, 1934).

Bioletti began writing the annual reports to the Regents under Hilgard in the late 1890's. Bioletti was an editor at the U.C. Experiment Station and read manuscripts of the proposed bulletins and circulars until he retired in 1935. 104 A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, p. 10, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Interviews conducted by Ruth Teiser and Joann Leach Larkey, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1973. Amerine praised his clear English and direct sentence structure. 105 Maynard A. Amerine, Professor Emeritus of Enology, FOREWORD, University of California, Davis, Grape and Wine Centennial Symposium Proceedings (1880-1980), p. IV (Department of Viticulture & Enology, UC Davis, January 1982).

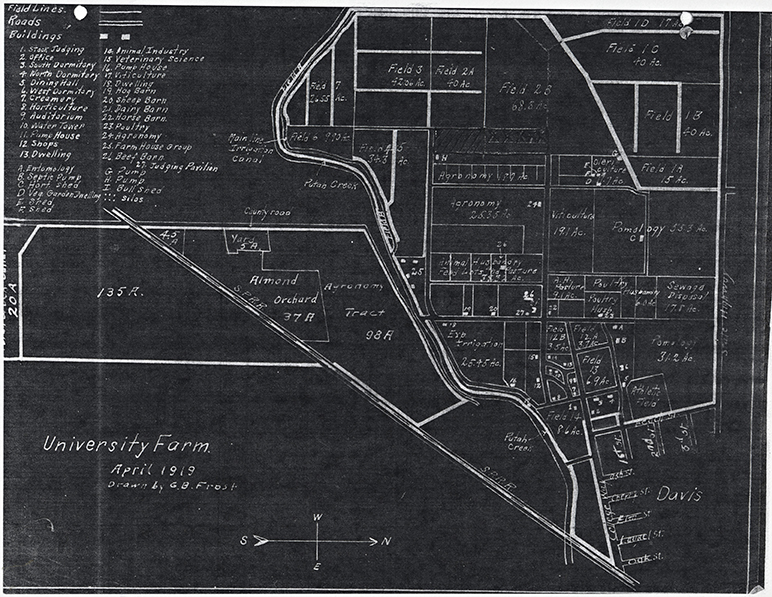

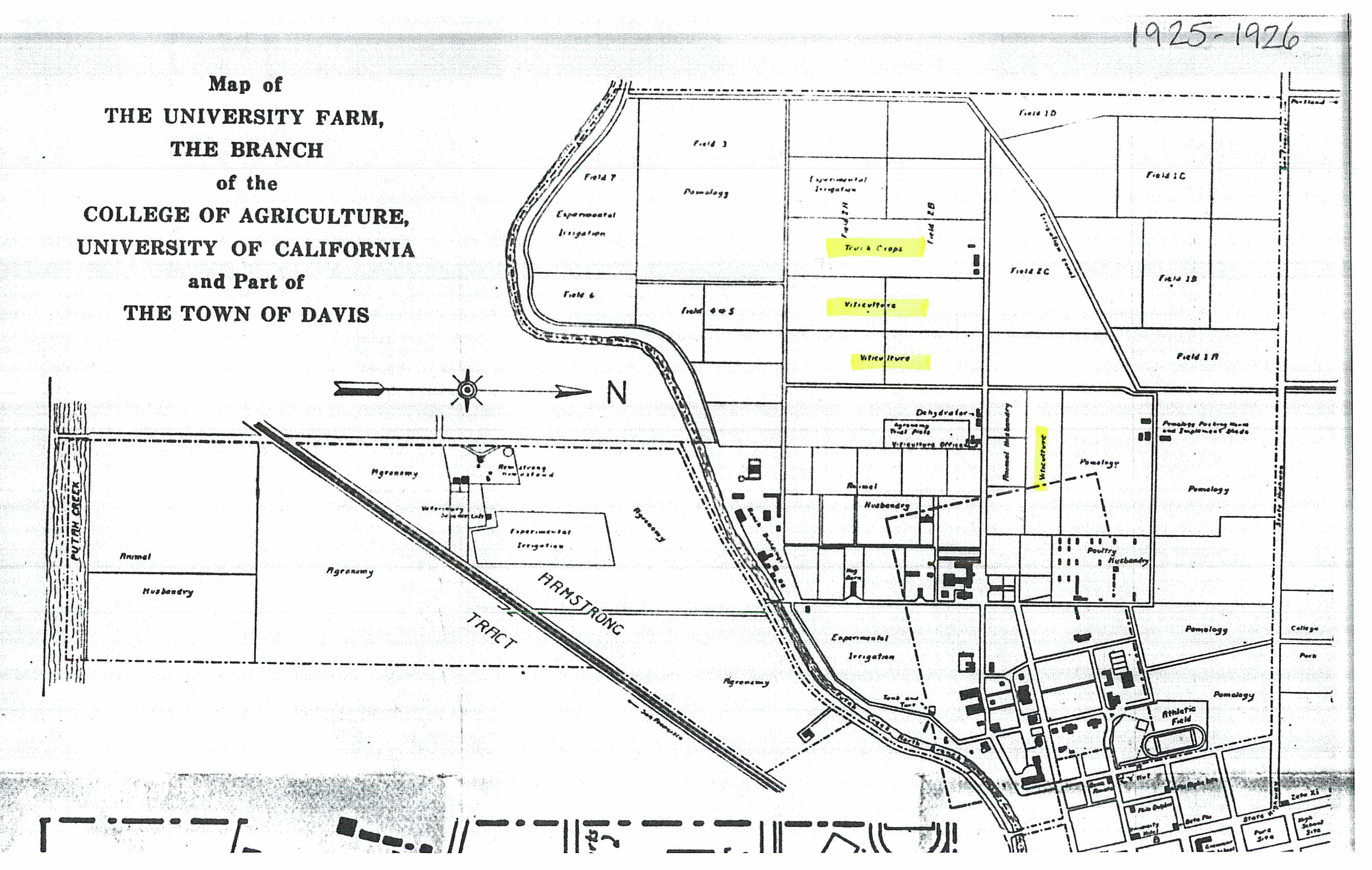

The University Farm

Edward J. Wickson served as successor to Hilgard as Dean of the U.C. College of Agriculture from 1905 to 1912. Wickson was a journalist (Pacific Rural Press) and lecturer in “practical agriculture”. While Dean, Wickson took on the job of selecting a site for the University Farm which was enabled by legislation passed in 1905. 106 Anne Foley Scheuring, “A Tale of Two Deans”, Science & Service, A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, pp. 61-65 (Regents of the University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1995). In 1906, a tract of land near “Davisville” in Yolo County was selected for the farm. It was important that the tract lay along a railroad line between Berkeley and Sacramento.Short courses and practical courses in horticulture and viticulture were offered as part of the curriculum in agriculture beginning after 1908. Bioletti would travel to Davis frequently in connection with his clonal selection work and other research projects.

107 Anne Foley Scheuring, Science & Service, A History of the Land-Grant University and Agriculture in California, pp. 69-70 (Regents of the University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 1995).

A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, pp. 67-68, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Interviews conducted by Ruth Teiser and Joann Leach Larkey, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1973.

Vines had been planted on the University Farm property on both sides of “Old Putah Creek” before the Division of Viticulture moved to Davis and set out to plant vineyards for use in their research work. To illustrate his oral history, Albert Winkler placed the Old Putah Creek Vineyard on a map in what appears to be in the general vicinity of Solano Park on the Davis campus (south of First Street, formerly known as College Way). 108 A.J. Winkler, Viticultural Research at University of California, Davis, 1921-1971, pp. 72A and 73, Oral History Program, California Wine History Series, Interviews conducted by Ruth Teiser and Joann Leach Larkey, Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1973. Vines in that area were used in some of the Short Courses in Viticulture offered around 1915.

From the University Archives Photograph Collection, Department of Special Collections, General Library, University of California, Davis. Images are the property of the Regents of The University of California.

Bioletti developed his Division (later Department) of Viticulture grapevine collection at the University Farm in Davis beginning in 1910. Although he was not permanently stationed at the new University Farm, Bioletti supervised two staff members who managed the instruction and viticultural research in Davis – Leon Bonnet from France and F.C.H. Flossfeder from Germany. Bonnet’s brother was at the time with Richter Nurseries in Montpellier, France. Several accessions in the new Davis vineyard were imported from Richter Nurseries.

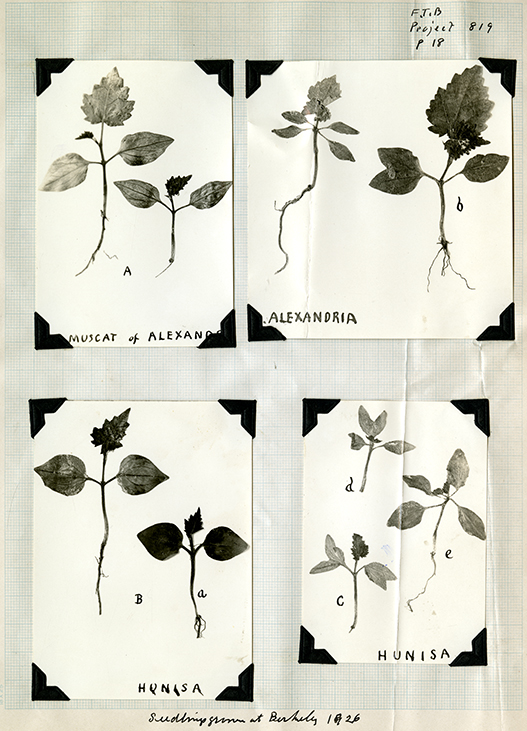

Records at UC Davis indicate that Bioletti initiated the planting of the new vineyards at Davis shortly after 1910. Those vineyard plans, drawings and plant lists are in a hardback notebook that is now housed as part of the Olmo collection (D-280) in Special Collections at Shields Library at U.C. Davis. 109 Bioletti, “Davis: Vineyard, Maps and Plans”’, Olmo collection D-280, Box 2: 11, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis.

The early vineyards planted at Davis were given numbers. The initial vineyard in the Bioletti notebook is Vineyard #1 (General Experiment Vineyard for teaching and research). 110 Olmo collection D-280, Box 23: folders 22-23, Department of Special Collections. Vineyard #1 contained Blocks A-H on a 19-acre parcel.

Plot D of Vineyard #1 is described beginning on page 10 of Bioletti’s notebook. 111 Olmo collection D-280, box 2: 11, Department of Special Collections. Plot D is designated the “Collection of Vinifera Varieties”, with vine planting lists shown initially through row 39. The notes indicate those vines were planted beginning 1910 or 1911. Source information was usually noted, either individually or for a group of vines. The sources included among others the U.C. Experiment Station at Tulare, Richter Nurseries in France and private growers around the state such as Fountain Grove in Sonoma County.

After the list of vines planted in Plot D in 1911, there are in the notebook several lists that describe cuttings needed in 1911-1912 for future plantings for Plot D. There are lists of cuttings to be brought from several different locations, e.g., Woodland, Pomona, Tulare. One list is entitled “Cuttings Needed from Miscellaneous (B, FG, F)” – Berkeley, Fountain Grove, Fresno. The desired sources for the “Miscellaneous List” are noted in Bioletti’s handwriting.