Written by Nancy L. Sweet, FPS Historian, University of California, Davis -

July, 2018

© 2018 Regents of the University of California

Malbec & Cot At FPS

A class of black wine grapes known as "Cots Rouges" is grown in southwest France. In the Middle Ages, powerful, dark wines made from black grapes grown in Cahors in the Valley of the Lot River were called "black wine" or "the black wine of Lot" by the English. The dominant grape cultivar in the "black wine of Lot" was a cultivar called Cot (Côt) or Malbec, which was grown in the rugged limestone vineyards of Cahors. 1 Robinson, Jancis, Julia Harding, and José Vouillamoz, WINE GRAPES, p. 272 (HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY, 2012); Mount, Ian, The Vineyard at the End of the World, Maverick Winemakers and the Rebirth of Malbec, pp. 220-221 (W.W. Norton & Co., New York and London, 2012); Baudel, José, Le Vin de Cahors, p. 102; 2nd ed., 1977 (in French); Viala, P., and V. Vermorel, Dictionnaire Ampélographie. Tome VI (Paris: Masson et Cie, 1905). Malbec/Cot is one of the six permissible cultivars allowed in red Bordeaux wines. (See chapter entitled "Black Grapes of Bordeaux").

Many historical references associate the "black wines" with medieval clergy and royalty. Wine from Cahors was reputedly served at the 1152 wedding of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England. In 1225, Henry III of England forbade Bordeaux authorities from stopping or taxing wines sent by Cahors merchants who were under his protection. Pope John XXII, who was born in Cahors in the 14th century, used vintages from that area as sacramental wines at Avignon. François I liked the wine from Cahors so much that he installed grapevines from that Quercy district in the vineyard at Fontainebleu in about 1531. Tsar Peter the Great preferred Cahors wine because he could tolerate it with his ulcerated stomach. 2 Mount, supra, at p. 220; Capdeville, Pierre (texte), Pierre Lasvènes, and Pierre Sourzat (photos), Le vin de Cahors, des Origines à Nos Jours, Dire Editions (Harmonia Mundi, Diffusion livres, 1999) (in French); Baudel, supra, at pp. 17-18, 30.

The wine grape cultivar known alternatively as Cot (France) and Malbec (New World) was present in University of California vineyards in the 1880's. The cultivar was important at that time as a blending variety in Bordeaux-style wines.

Malbec has been developed into a successful varietal wine in its own right, most notably in Argentina. Recent plantings in the United States demonstrate increased interest in the cultivar in this country, particularly amongst the younger generations of wine drinkers.

The origin and parentage of Malbec

The cultivar now known most commonly as Malbec was given many different names in central and southwestern France. French ampelographer Pierre Galet amassed more than 1,000 synonyms. The cultivar is known as Cot in the Loire Valley, Pressac in the Libournais area of Bordeaux, Malbec or Malbeck doux in the Gironde, Luckens or Lutkens in the Médoc or Graves, Coté rouge in Entre deux Mers and Lot-et-Garonne, and Auxerrois or Cot noir in the Cahors area of Quercy. 3 Galet, Pierre, Grape Varieties and Rootstock Varieties, pp. 82-84 (Oenoplurimédia sarl, Château de Chaintré, France, 1998).

The geographical origin of Malbec is not known with certainty. The confusion was compounded by the numerous synonyms used for the cultivar throughout France. Multiple theories have proposed alternatives such as Hungary, Germany and regions all over France.

Hypotheses as to the geographical origin of the cultivar were initially based on the various names and synonyms by which the cultivar was known in France. Names used for Malbec in the Médoc and Graves areas in the 18th century were Estrangey, Etrangey or Etranger (foreigner), hinting that the original home of the cultivar was other than the Gironde region. 4 Galet, 1998, supra, at p. 82. One ampelographer specializing in German grapevines, Jean Louis Stoltz, speculated that the cultivar came from the banks of the Rhine under the name Agreste. 5 Galet, 1998, supra; Viala et Vermorel, 1905, supra, at p. 7.

Some of the names attached to the cultivar in southwest France were adopted from the name of the person who introduced the grape to a particular area. A M. de Lutkins, who was a doctor in Bordeaux, planted the cultivar in Camblanes in the Gironde in the 18th century; the synonym name Luckens or Lutkens is thus used for Malbec in the Médoc and Graves area. 6 Viala et Vermorel, supra, at p. 7. A man named Pressac brought the cultivar to the Libournais area near St. Émilion; Malbec is known as Pressac or Noir Pressac in that region of Bordeaux. 7 Robinson, Jancis, The Oxford Companion to Wine, 3rd ed., p. 421 (Oxford University Press, Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, 2006); Galet, 1998, supra.

The name Malbec first became associated with the cultivar as a result of another independent introduction. Oral history in Bordeaux holds that a Hungarian viticulturist named Malbeck or Malbek brought the grape to the Médoc/Gironde in the Left Bank region of Bordeaux, where the winemakers blended it into claret for the dark juice quality. 8 Mount, supra; Leclair, Philippe, “Clonal selection of Bordeaux varieties”, In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Clonal Selection, pp. 12-16 (J.M. Rantz (ed.), Am. Society for Enology and Viticulture, Davis, CA, 1995); Viala et Vermoral, supra, p. 7.

Most sources concluded Malbec originated in the vineyards surrounding the Lot River in southwest France near the town of Cahors. Cahors is about 70 miles north of Toulouse in the Quercy region. The cultivar was once known there as Cot or Cot noir. Galet explained that the name “Cot” evolved as a progressive transformation of the name of the town Cahors – illustrated by the following names that are also used in the region: Côte rouge, Costo roujo and Cot. 9 Galet, 1998, supra, p. 82; see also, Robinson et al., 2012, supra, at pp. 272-273.

At one time, a few authors proposed a Burgundian theory of origin for the cultivar, which has also been known for many years in the Cahors area by the name Auxerrois. 10 Robinson, 2006, supra. Some authors, including French ampelographer Louis Levadoux, concluded that use of the synonym name Auxerrois meant that Cot originated near the town of Auxerre in the departement of Yonne in Burgundy. Speculation continued that the cultivar then migrated from Yonne to southwest France via the Loire Valley, where it received the name Côte in Poitou and Touraine. This theory assumes that the people in southwestern France did not recognize a long “o” and mispronounced the name “Côte” as “Cot” once it got to the Cahors area. 11 Galet, Pierre, Cépages et Vignobles de France, Tome II: L’Ampélographie Française, p. 104 (2e Édition, Imprimerie Charles DEHAN, Parc Euromédicine, Montpellier, 1990). (in French)

The Burgundian theory was rejected by Galet, noting that the Malbec cultivar was not historically grown in vineyards in Yonne except for a few acres in a town called Joigny. The presence of the cultivar in the Yonne region of Burgundy was explained by Galet as the result of growers in Cahors sending cuttings to the area around Auxerre by order of the King (who had also requested that vines be planted in the nearby Château of Fontainebleu). The reasoning went that growers in Cahors named the cultivar Auxerrois after it was sent to Auxerre, Burgundy. 12 Galet, 1990, supra, p. 105.

Use of the synonym Auxerrois for this black grape cultivar causes confusion in another fashion. Auxerrois is also the name of a Burgundian white grape cultivar that is a full sibling to Chardonnay, whose parents were Pinot and Gouais blanc. 13 Bowers, John, Jean-Michel Boursiquot, Patrice This, Kieu Chu, Henrik Johannson, and Carole Meredith, Science, vol. 285, page 1562 (September 3, 1999). Recent DNA results show that the parents of Malbec were not Pinot and Gouais blanc.

Results of a DNA analysis from France in 2009 showed that the best candidate for the geographical origin of Malbec is southwestern France near Cahors in the Lot Valley. 14 Robinson et al., 2012, supra, pp. 272-274. The analysis revealed that Malbec and Merlot share the same female parent, a long-forgotten cultivar recently renamed Magdeleine Noire des Charentes. The male parent of Malbec is Prunelard, an old and endangered cultivar from southwest France. 15 Boursiquot, J.-M., T. Lacombe, V. Laucou, S. Julliard, F.-X. Perrin, N. Lanier, D. Legrand, C. Meredith and P. This, “Parentage of Merlot and related winegrape cultivars of southwestern France: discovery of the missing link”, Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research 15: 144-155 (2009).

The plant material recently named Magdeleine Noire des Charentes was introduced into the INRA grape germplasm repository of Domaine de Vassal (Montpellier, France) for the first time in 1996. The cuttings for the accession were taken from an abandoned grapevine growing on a hill in northern Brittany; the cultivar was known to be growing in that area in the second half of the 15th century during the Middle Ages. Additional cuttings were retrieved by the researchers in 2004-2007 from four different villages in Charentes in central-western France - 400 km from Brittany and adjacent to the Loire Valley. 16 Boursiquot et al., supra. The name Magdeleine Noire des Charentes was developed from the local names used by the growers in the villages in Charentes. Magdeleine Noire de Charentes had for unknown reasons escaped notice of ampelographers when French grape cultivars were described and referenced in the 19th century.

The paper that identified the parentage for Malbec proposed its geographical origin through an analysis of five progeny cultivars of Magdeleine Noire des Charentes, the mother of Malbec and Merlot. The five progeny cultivars (including Malbec) have five different fathers. Based on descriptions in the classic ampelographical work of Viala et Vermorel and the locations from which the five progeny cultivars were collected prior to introduction into the Domaine de Vassal repository, the researchers placed the “supposed geographical origins” of all five progeny cultivars in southwestern France. In so doing, they include Charentes (home of one of the progeny cultivars) within the designation “southwestern France”. 17 Boursiquot et al., supra; Viala et Vermorel, 1905, supra, p. 7.

The conclusion that Malbec originated in southwest France is qualified a bit by the reference to Viala et Vermorel. That work suggests two possible origins for Malbec, only one of which is considered “southwest France”: (1) Quercy (Cahors) in southwest France and (2) Touraine, which is in the Loire Valley. Nevertheless, a strong inference can be drawn in favor of an origin in southwest France for Malbec, given that its male parent Prunelard had a known presence in that region. No mention is made of Prunelard in the Loire Valley. 18 Boursiquot et al., supra; Viala et Vermorel, 1905, supra, p. 7.

Malbec was widely planted in Bordeaux and was important in winemaking in that region prior to the 19th century. During the 19th century, the style of Bordeaux wines underwent a major change from Malbec to Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot due in part to the failure of the Malbec crop for several consecutive years of bad weather. At the same time, a naval blockade during the Napoleonic Wars (~1811) caused a switch from the milder Baltic oak barrels in which the Malbec-Verdot blends matured to barrels made of French oak, which had a greater effect on the wine and became the preferred oak for the Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot blends. 19 Asher, Gerald, “Châteaux Margaux: Time Recaptured”, The Pleasures of WINE, p. 66 (Chronicle Books, San Francisco, California, 2002).

Several other forces negatively impacted Malbec acreage in Bordeaux. The 19th century phylloxera epidemic and a 1956 killer frost in southwest France contributed to reduced acreage. 20 Mount, 2012, supra, p. 221. Finally, the cultivar reportedly fell out of favor because of poor fruitset (excessive number of abscissed berries) which was attributed to virus infection in the 1950’s. 21 Leclair, supra.

After the 1956 frost, Cahors became France’s main producer of Malbec, which is appreciated there for the color, aromas, tannins and acidity that it gives the wines. 22 Attia, F., F. Garcia, M. Garcia, E. Besnard, and T. Lamaze, “Effect of Rootstock on Organic Acids in Leaves and Berries and on Must and Wine Acidity of Two Red Wine Grape Cultivars ‘Malbec’ and ‘Négrette’ (Vitis vinifera L.) Grown Hydroponically”, Proc. Intl. WS on Grapevine, eds. V. Nuzzo et al., Acta Hort. 754, ISHS 2007. Cahors was awarded full Appellation Contrôlee status in 1971; appellation rules provide that the Malbec cultivar, known in Cahors as Auxerrois or Cot, must be at least 70% of the wine, blended with Tannat or Merlot. 23 Robinson et al., 2006, supra, p.122. The clones contained within the vineyards of Cahors (French Cot clones 42, 46, 594, 595, 596, 597 and 598) date from the 1970’s. 24 Anonymous, “Two new International Events Dedicated to the Malbec Grape”, Wine Business Monthly, vol. XVII no. 3, page 54, March, 2010.

Malbec is a minor variety in France in 2018 and is produced in Bordeaux and the Loire Valley, in addition to Cahors. 25 Mount, 2012, supra, p. 221; Grimshaw, Susie, “Malbec, the resurrection of France’s forgotten wine”, The Guardian, May 21, 2010; Weber, Edward, “Malbec”, p. 75, Wine Grape Varieties in California, eds. Christensen, L.P., N.K. Dokoozlian, M.A. Walker, and J.A. Wolpert (University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Oakland, CA, 2003). Clonal selection programs in Bordeaux have reportedly eliminated grower concern about Malbec’s fruit set problems in that region. 26 Leclair, supra. Malbec remains one of the six permissible grape varieties allowed in red Bordeaux wine, where it is used primarily as a blender in small amounts with Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet franc, Carménère, and Petit Verdot.

Success in Argentina

A book by Ian Mount, The Vineyard at the End of the World: Maverick Winemakers and the Rebirth of Malbec, thoroughly chronicles the history and development of Malbec in Argentina. Argentina became a wine powerhouse in the last decades of the 19th century, becoming the world’s fifth-largest producer of wine by 1915. Ultimately, winemakers in that country developed a “fine varietal wine” from what Mount refers to as “an unloved grape with unlovely name: Malbec”. 27 Mount, Ian, The Vineyard at the End of the World, Maverick Winemakers and the Rebirth of Malbec, pp. 25, 70 (W.W. Norton & Co., New York and London, 2012); Robinson, 2006, supra, p. 29.

Vitis vinifera plant material was introduced into Argentina starting in the 1550’s directly from Spain and via other South American regions. Grapes, primarily Cereza and Criolla, have been grown in the eastern foothills of the Andes, including the area around Mendoza, since that time. 28 Robinson, 2006, supra.

A more significant importation of vinifera occurred much later, in the 19th century. A colorful personality from Tours named Michel Aimé Pouget emigrated from France to Chile around 1850 when Louis Napoléon declared himself Emperor of France. Pouget was an agricultural engineer who took to South America cuttings of classic French grapes, including Malbec, which was at the time important in Bordeaux. In 1853, Pouget was ultimately persuaded to move to the Mendoza area in Argentina to operate a government model farm. He carried with him knowledge of modern agricultural and winemaking techniques, as well as cuttings of Malbec and other classic French grapes, which were thereafter planted along the desert region of western Argentina. 29 Mount, supra, pp. 41-44.

The wine industry was developed slowly in those early centuries. In the late 19th century, improved irrigation techniques and an influx of European immigrants familiar with viticulture and wine-making facilitated the improvement of the industry and influenced tastes. Eventually, Mendoza became the largest and arguably most important wine-growing province in Argentina. 30 Robinson, 2006, supra, p. 31.

Mount explained that Malbec thrives in the climate and geography of western Argentina, particularly in the arid high-altitude valleys. Growers have observed that older Malbec vines in Mendoza’s higher altitude areas produce Malbec grapes with intense color, flavor and structure. Malbec is a thin-skinned grape that is susceptible to cold and disease. The cultivar thrives in the hot sun in Mendoza, most likely because of its high vigor and dense leaf cover. That warm evening temperatures contribute to reduction of grape acids, so that Malbec in Argentina is not as acidic as that in France. 31 Mount, supra, pp. 221-233; Walker, M. Andrew. 2012. Email communication with author, August 31, 2012.

Malbec acreage in Argentina increased until it peaked at 120,000 acres in the 1960’s. From 1970 through 1990, Malbec acreage decreased to 25,000 acres and prices became depressed. Vineyards with gnarled old Malbec vines were pulled in favor of other varieties that produced high yields for bulk wines. Additionally, those Argentinian winemakers who chose to compete internationally with fine wines favored other more traditional red vinifera varieties at first.

Mount reported that it was not until the mid-1990’s that high quality Malbec was produced as a varietal wine in Argentina. Malbec grower/winemaker bodegueros such as Domingo Catena saw the potential for Malbec as a fine wine. His son, Nicolas, eventually gambled on that potential and, Bodega Catena Zapata led the movement toward fine Malbec wines when he produced them beginning in 1994. 32 Mount, supra.

The grapes that were used for those wines were selected in Mendoza from the successor vines of Argentinan grapes planted in the mid-19th century, as well as from grapevine material brought anew from Cahors. 33 Mount, supra, p. 233; Catena Zapata website, http://www.catenawines.com/eng/family.html. The goal of the selection program was development of the best clones for each altitude, favoring healthy looking grapes with small berries and clusters, lower yields and fewer shot berries to produce concentrated flavors. 34 Cutler, Lance, “Making Malbec, How Argentine vintners craft their hot varietal”, Wines & Wines magazine, October 2007. The ultimate formula for production of fine Malbec wine in Argentina has been described as: material from old, carefully selected vines; grown for low yields, at high altitudes in intense sun and rocky soil; with the use of new wine production technologies. 35 Mount, supra, pp. 233-271.

By 2011, Malbec acreage in Argentina rebounded to ~77,000 acres, 85% of which were in Mendoza. 36 Robinson et al., WINE GRAPES, 2012, supra, p. 273-274. Malbec’s popularity as a fine varietal wine caused exports to increase. The Wine Market Council and Nielsen reported that Argentina and New Zealand were leaders in table wine import growth in the United States in 2011, with Moscato, Pinot noir and Malbec as the top three varieties. 37 Korman, Alexis, “Wine’s 2011 Report Card”, Wine Enthusiast Magazine, published February 1, 2012, www.winemag.com/Wine-Enthusiast-Magazine/Web-2012/Wines-2011-Report-Card/ . Jancis Robinson has referred to Malbec as “Argentina’s most important serious wine grape” that has become “Argentina’s vinous trademark”. 38 Robinson, 2006, supra, pp. 32, 421.

Malbec in California

Information on the first importation of Malbec into California is sparse. What is known is that in the 1850’s several French immigrants saw the need for higher quality wine grapes in the state and brought cultivars from Bordeaux to California. 39 Hilgard, E.W. (1892), Report of the Viticultural Work during the Season of 1887-1889 with data regarding the Vintage of 1890. Part I. Red-wine grapes, pp. 31, 20-52, Report to the Regents, Agr. Exp. Sta., University of California, 1892.

Jean-Louis Vigne in Southern California was the first immigrant to import varieties from Bordeaux in 1833, however, records of what varieties he established and whether they survived do not exist. 40 Walker, M. Andrew, “UC Davis’ Role in Improving California’s Grape Planting Materials”, Proceedings of the ASEV 50th Anniversary Annual Meeting, Seattle, Washington, June 19-23, 2000; Pinney, Thomas (1989), A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition, volume 1, pp. 246-248 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989). Red wine varieties used to make “claret” were first brought to Northern California from France’s Bordeaux region in the 1850’s by Santa Clara Valley Frenchmen Antoine Delmas, Pierre Pellier and Charles Lefranc. 41 Sullivan, Charles (2008), Napa Wine, A History, p. 136 (The Wine Appreciation Guild, South San Francisco, California, 2008). Although Delmas imported thousands of cuttings from France in 1854, available authorities do not specifically state that Cot or Malbec was among them. The date and cultivar list for the early Pellier importation are similarly vague. 42 Sullivan, Charles (1982), Like Modern Edens, Winegrowing in the Santa Clara Valley and Santa Cruz Mountains, 1798-1981, p. 21 (California History Center, Cupertino, CA, 1982).

There is authority indicating that Charles Lefranc imported Malbec from France to California either in 1857 or 1858. Lefranc was a French immigrant who established the New Almaden Vineyard near San Jose in the Santa Clara Valley. In 1857-1858, he imported cuttings of important wine grapes, including Malbec, to plant in his vineyard and sell commercially. 43 Sullivan, 2008, supra, p. 136; Weber, 2003, supra, p. 75; Sullivan, 1998, supra, p. 188.

In his 1861 trip to Europe, Colonel Agostin Haraszthy reportedly brought from France all grape cultivars used to make Bordeaux clarets. The catalogue of cultivars imported during that trip includes Malbec, which was supposedly thereafter planted in his vineyard at Buena Vista Ranch in Sonoma County. However, it is thought that the cultivars were probably not widely distributed otherwise. 44 Sullivan, Charles L. (2003), Zinfandel, A History of a Grape and its Wine, pp. 56-57 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 2003); Wetmore, Charles A. (1881), First Annual Report of the Chief Executive Viticultural Officer of the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners for 1881 (2nd ed. – revised, Sacramento, California, published 1881), Appendix I, p. 184.

Charles Wetmore was the Chief Executive Viticultural Officer of the Board of State Viticultural Examiners at that time. He wrote in the First Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer (1881) in the section entitled “Classification of California Wines”: “I have yet failed to find good reasons, excepting the scarcity and high price of cuttings, for the neglect to sufficiently cultivate in all the Sonoma and Napa vineyards, which can nearest approach the Bordeaux, the varieties which give character to the finest Bordeaux red wines. The Carbenet [sic.] Sauvignon and the Malbec have been too long ignored.” 45 Wetmore, 1881, supra, pp. 65-66.

Wetmore reported that Lefranc’s old Malbec vines were the only large planting of good red Bordeaux vines in California prior to the 1880’s. 46 Wetmore, Charles A. (1884), Second Annual Report of the Chief Viticultural Officer to the California Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, for the years 1882-83 and 1883-84, with three appendices, including Part V (Ampelography), Sacramento, California, published 1884. U.C.’s Professor of Agriculture Eugene Hilgard recognized Lefranc’s Malbec block at New Almaden as “the largest area of Malbeck in the State thus far [1884]”. 47 Hilgard, E.W. (1886a), Report of the viticultural work during the seasons 1883-1884 and 1884-1885, being Appendix IV to the Report to the Regents for the year 1884; with notes regarding the vintage of 1885-1886, p. 83. The Santa Clara plantings were not large enough to satisfy the demand of the market.

Small lots of wine containing Malbec and other Bordeaux varieties were produced in California between 1860 and 1880. Charles Lefranc was a winemaker in addition to a viticulturist. He made the first commercially successful California “Médoc” in the 1860’s, which he called “Cabernet-Malbeck”. Wetmore observed that the “Cabernets and Malbecs” were mixed in Lefranc’s vineyards. 48 Sullivan, 2008, supra, p. 136; Wetmore, 1881, supra, p. xxxii.

The “Malbecks” and claret (blended with Cabernet Sauvignon) wines made in the 1860’s and 1870’s were highly regarded by Wetmore and Hilgard for the color, bouquet and general character. 49 Sullivan, 1982, supra, pp. 24-26; Wetmore, 1884, supra, p. 40 and Part V (Ampelography). Hilgard wrote of Lefranc’s “Malbeck” of 1881 and several other 1870’s Santa Clara “Malbecks”: “[they] prove irrefragably the excellent keeping power of the color of that wine, and a beautifully rounded mellowness in their taste”. 50 Hilgard, 1886a, supra, pp. 83-84.

Malbec and other Bordeaux varieties began to appear in vineyards outside Santa Clara County around this time. Glen Ellen’s J.H. Drummond planted the first plot of useful Bordeaux vines in the North Coast in 1878. He was soon followed by Napa’s H.W. Crabb. By 1885 virtually every major producer who was interested in fine claret had Cabernet Sauvignon, and many also grew blending cultivars such as Malbec. Crabb favored Malbec at first but then turned to Cabernet franc to use as a blender. Gustav Niebaum first used Merlot and Verdot for blending, but cellar records indicate that he later favored Malbec. 51 Sullivan, 2008, supra, p. 136. Other notable plantings of Malbec were made by the Natoma Land and Water Company in Folsom and by Charles Wetmore himself in Livermore. 52 Wetmore, 1884, supra.

Charles Wetmore authored an important document in 1884 entitled Ampelography, in which he reviewed the winegrape varieties then being grown in California and recommended what he saw as appropriate quality cultivars for use in varietals or blends. He initially identified “the proper Malbeck (Cot de Bordeaux)” as one of several varieties generally included within the name Cot. 53 Wetmore, 1884, Part V (Ampelography). Wetmore highly valued Malbec wine and recommended the cultivar for use in California clarets. He ultimately opined that “Malbeck” would be appropriate for planting in the coastal regions of California and did not believe the cultivar would succeed in areas of great heat and sudden extremes of temperature. 54 Wetmore, 1884, supra.

The University of California evaluated appropriate grapes and wines for California beginning in the 1870’s. Malbec was one of the cultivars included in those evaluations, as well as in early plantings in the University experiment station system.

The lack of funding for University stations in the early 1880’s forced Hilgard to arrange for privately funded sources of grapes and wine to assist with university viticulture work. Donated samples used in university research included Hilgard’s own vineyard at Mission San Jose, Crabb and Krug in Napa, Drummond and Gundlach in Sonoma, Lefranc and others in Santa Clara, the Natoma Water and Mining Co. in Folsom, George West in Stockton, and Professor Eisen in Fresno. “Malbeck” grapes and wine samples were sent to the university for analysis from Crabb, John Doyle, Lefranc, Wetmore, and M. Keatinge in Lower Lake County. The Natoma Water and Mining Co. in Folsom imported 40 cultivars from Europe and planted them in 1883. Natoma donated sample lots of wines of 40 cultivars (including Malbec) to the university lab for analysis in 1884 and 1885. 55 Hilgard, 1886a, supra, pp. 54-83; Hilgard, E.W. (1886b), Report of the viticultural work during the seasons 1885 and 1886, being Appendix VI to the Report to the Regents for the year 1886, pp. 9, 13; Hilgard, E.W. (1884), Report of the Professor in charge to the President, being a part of the Report of the Regents of the University, 1884, pp. 9, 13; Hilgard, E.W. (1880), Report of the Professor in Charge to the Board of Regents, College of Agriculture being a part of the Report of the Regents of the University, 1880, pp. 88-89.

Hilgard believed that Malbec had potential for California wines and from the outset included it in the grapes that were studied by the university. 56 Hilgard, 1886a, supra, p. 83. He wrote that, “although California growers and winemakers were familiar with Malbeck by that time [1884], the cultivar had not previously been more widely cultivated in in the state due to its tendency to light bearing.” 57 Hilgard, 1886a, supra, pp. 83-84.

Ultimately five general culture (experiment) stations were established within the University: the Central Station at Berkeley (in operation since ~1880), the Sierra Foothill Station near Jackson in Amador County, The South Coast Station near Paso Robles in San Luis Obispo County, The San Joaquin Valley Station in Tulare County, and the South California Station in Pomona. Viticultural work also continued at three special (privately owned) stations at Cupertino, Mission San Jose and Fresno. 58 Hilgard, E.W. (1891), Report of Work of the Agricultural Experiment Stations of the University of California for the Year 1890, being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University, Sacramento, 1891. In 1884, a close friend of Hilgard’s named John T. Doyle assigned to the University some of his property in Cupertino for use as an experiment station vineyard. The two-year-old vines on the property consisted of forty varieties from around the state including “Malbeck”. That privately-funded station became known as the West Side Santa Clara Valley Station in Cupertino. 59 Hilgard, 1886a, supra, p. 160; Hilgard, 1886b, supra, p. 124.

Evaluation of appropriate grape varieties for California continued in the new University experiment station system. Grapes were grown at each of the five general culture stations, as well as the three private viticultural stations. Malbec and other Bordeaux type grapes were grown in the experiment station vineyards at Berkeley, Jackson, Paso Robles, Tulare, and the private stations in Cupertino and Mission San Jose. No source information is available for the Malbec planted at the four general culture stations. There was no Malbec in the southern California station at Pomona. 60 Hilgard, E.W. (1890), Report on the Agricultural Experiment Stations of the University of California with Descriptions of the Regions Represented, being a Part of the Combined Reports for 1888 and 1889, Sacramento, California, Appendix No. 4, p. 197.

In 1892, Hilgard concluded that Malbec was shown to be early maturing but a low producer. Small wine lots were made. Except for wines from very young and short pruned vines, Hilgard noted that Malbeck maintained its character in terms of high sugar and alcohol content, heavy body, deep color, high tannin and low acidity from old vines with well-matured fruit. However, the researchers had great difficulty in maturing the wines “without their acquiring the lactic taint”, which Hilgard attributed to samples that were badly coulured (failure to set fruit or fruit drop). He concluded that more reliable and abundant bearers should be used for blending with Cabernets. 61 Hilgard, 1892, supra, p. 38

In 1896, in a summary of the results of the years of testing and observation, Hilgard observed that “Malbeck” showed poor yields and serious coulure at all the experiment stations. It seemed best adapted at Paso Robles. Hilgard concluded that Malbeck was completely ill suited for conditions such as those in Tulare and the San Joaquin Valley. Malbec was not recommended for California vineyards by the University, even as a blender with Cabernet Sauvignon. 62 Hilgard, 1892, supra, p. 31; Hilgard, E.W. (1896b), Report on Viticultural Work during the Seasons 1887-1893 Being a Part of the Report of the Regents of the University, Data Regarding the Vintages of 1894-95, Part I.a., Red Wine Grapes, Sacramento, 1896; Hilgard, E.W. (1896a), Bulletin 111, Work of the College of Agriculture & Experiment Stations, University of California, Berkeley, California, September, 1896.

University observations in the 20th century

Malbec did not receive more favorable reviews in University publications in the first half of the 20th century. The cultivar was not recommended for commercial planting in California in Frederic Bioletti’s 1907 Experiment Station Bulletin entitled “The Best Wine Grapes for California” (Bulletin no. 193), even as a blender for Cabernet Sauvignon.

However, Malbec was among the varieties included in selection blocks and the variety collection when Bioletti planned the new vineyards for the Division of Viticulture at the University Farm in Davis in 1910. One of the current FPS Malbec selections originated from that early vineyard at Davis.

During the period of Prohibition, very little research on wine grapes was done at the University, although some of the better vineyards were maintained in the state. Bioletti did not mention Malbec in the chapter “The Grape Varieties in California”, a 1929 Extension Circular that reviewed the merits of California red and white wine grapes. 63 Bioletti, Frederic T. 1929, rev. 1934. Elements of Grape Growing in California, p. 26, California Agricultural Extension Service, Circular 30, March, 1929 (rev. April, 1934), College of Agriculture, University of California, Berkeley; Bioletti, F.T. (1907), “The best wine grapes for California”, Calif. Exp. Sta. Bul. 193: 141-145 (1907).

UC Professors Maynard Amerine and Albert Winkler mentioned Malbec only in passing in their 1944 Hilgardia magazine review of wine grapes in California. The cultivar was not tested in the coastal counties in the research described in that article. Planting of Malbec in California vineyards was not recommended at that time on the basis that “other varieties have equal or greater potentialities”. Further study of the acidity of the Malbec in cooler growing regions such as the coastal counties was suggested as a possibility. 64 Ough, C.S., and C.J. Alley. Undated. Cabernet-type Grapes and Wines from the Coastal Regions of California, Department of Viticulture and Enology, University of California, Davis; Amerine, M.A. and A.J. Winkler (1944), “Composition and Quality of Musts and Wines of California Grapes”, Hilgardia 15: 493-673, February 1944.

Amerine and Winkler issued another comprehensive set of recommendations on California Wine Grapes in 1963. After some study, Malbec was again not recommended for California vineyards. The research showed that Malbec production levels were moderate and irregular, and malic acid levels were low. The authors concluded that the variety was a poor grape for California region IV (interior Central Valley with marine influence) and of “doubtful utility for the cooler regions”. They thought that the cultivar’s “slight Cabernet-like aroma” could make it useful in blends if it were fermented with another variety. 65 Amerine, M.A. and A.J. Winkler (1963), California wine grapes. Composition and quality of musts and wine, Calif. Agr. Exp. Sta. Bul. 794: 1-83 (1963).

Malbec Plantings in California

Malbec was popular in northern California before 1900 for blending with Cabernet Sauvignon. 66 Sullivan, Charles (1998), A Companion to California Wine, p. 199 (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California, 1998). California grapevine acreage declined sharply in the late 1800’s due to phylloxera. Malbec was planted little in the phylloxera-devastated vineyards until much later. 67 Weber, supra; Sullivan, supra.

Malbec did not have a “commercial presence” in California in 1964. However, the cultivar was planted in the vineyards of the University of California at that time. 68 Olmo, H.P., “A Check List of Grape Varieties Grown in California”, Am J. Enol. Vitic. 15: 103-105 (1964). Malbec began appearing by name in grape acreage statistics in California after five acres were planted in Napa in 1976. The total number of Malbec acres in the state in 1978 was estimated at 134 (bearing and nonbearing). 69 California Grape Acreage 1978, California Crop and Livestock Reporting Service, Department of Food & Agriculture, Sacramento, CA. Acceptance of Malbec by growers was traditionally limited by the fact that the cultivar is subject to poor fruit set. 70 Weber, supra; Sullivan, supra.

Total Malbec acreage in California increased slowly and steadily during the latter part of the 20th century. In the period between 2009 and 2011, Malbec acreage increased rapidly to a total of 2,041 acres (1,611 bearing and 430 non-bearing) in the state. 71 California Grape Acreage Report, 2011 Summary, California Department of Food & Agriculture in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, March 30, 2012, www.nass.usda.gov/ca . By 2017, the total acreage for Malbec reached 3,822 acres (bearing and non-bearing). 72 California Grape Acreage Report, 2017 Summary, page 5 of 6, released April 19, 2018, California Department of Food & Agriculture, cooperating with the United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Sacramento CA, www.nass.usda.gov/ca.

The increased interest in Malbec after 2000 was attributable in part to California growers and winemakers searching for different and interesting grape cultivars for winemaking. Some planted what they called a “Meritage scheme”, a blended group of Bordeaux cultivars adopted as an alternative to pure varietal wines. Those cultivars included Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet franc, Petit Verdot and Malbec, which were planted in Napa and other areas of the state for use in wines sold as “Meritage” blends. 73 Sullivan, 2008, supra, p. 386; Robinson, 2006, supra, p. 437; Pinney, Thomas (2005), A History of Wine in America: From Prohibition to the Present, volume 2, pp. 342-343 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Additional interest was sparked by the success of Malbec as a varietal wine in Argentina. The recent popularity of Malbec wine, especially among younger wine drinkers, has been attributed to the “big, ripe fruit and nice structure Malbec delivers at a very affordable price”. 74 Zimmerman, Lisa B., “On Premise: Feisty Malbec”, Wine Business Monthly, vol. XVII No. 3, pages 50-53, March, 2010.

MALBEC & COT SELECTIONS AT FPS

Foundation Plant Services at the University of California, Davis, maintains a virus-tested foundation vineyard containing 24 public and proprietary Malbec/Cot selections in 2018. The publicly-available Malbec selections originated from vineyards in France and California, including the old University vineyards planted in the early 20th century.

The FPS public selections for this cultivar are named Malbec, because that is the name by which the cultivar is most popularly known throughout the world. The proprietary French clones at FPS are named Cot by request of the owner. The proprietary Argentine clones are known by the name Malbec, the preferred name for the cultivar in the New World.

Malbec 04

Malbec FPS 03 and Malbec FPS 04 originated from the same source vine in the “Old Foundation” (O.F.) vineyard at the University of California, Davis. That vineyard was located in the “Armstrong” (also “West Armstrong”) tract at Davis. The source vine for the two selections was planted at location “O.F.A r9 v3” in that vineyard in 1955 under the name “Cot (Malbec)”. The plant material at O.F. A9v3 was one of the early clones identified by Dr. Harold Olmo (UC Department of Viticulture & Enology) in a systematic effort to acquire European grape cultivars for the grape and wine industry.

In 1934, plant pathologist William B. Hewitt was hired by the University of California to deal with the Pierce’s Disease problem in vineyards throughout the state. Eventually, both Hewitt and Olmo (who was at the time working on breeding Pierce’s Disease resistant grapevines) expanded their work to deal with grapevine viruses, particularly leafroll and fanleaf. 75 Alley, L., D. Golino, and A. Walker (2000-2001), Retrospective on California Grapevine Materials, Part I: Problem’s Facing California’s Growers, (November, 2000); Part II: Problems facing California’s growers (January, 2001); Part III: Solutions for a growing industry (April, 2001), Wines & Vines magazine, 2000-2001.

Stricter plant quarantine regulations were established around 1948 by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), ending “uncontrolled importation of clonal plant materials” and requiring a permit for importation of any Vitis spp. into the United States. The regulations provided that imported grapevine material could not be released until it was tested for viruses, thus necessitating plant quarantine facilities. In 1950, no one at the national level knew how to test for grape viruses, so the USDA quarantine greenhouses in Maryland were overflowing with untested cuttings, which would either die or be in very poor shape by the time of their release many years later. Olmo and Hewitt worked to establish a quarantine facility at Davis, so that upon arrival in the U.S., vines could be shipped directly to that facility and be supervised there during the quarantine testing process. 76 Alley, L. et al., 2000-2001, supra. Their efforts beginning in 1952 eventually resulted in the Foundation Plant Services facility at UC Davis in 1958.

At the same time, there was much interest in improved grapevine material. Prohibition (1920-1933) had decimated the California vineyards that contained high quality wine grape cultivars. Harold Olmo convinced industry members that a concerted effort should be undertaken to import known grape cultivars from the areas in which they had thrived. In 1951, the California Wine Institute funded a trip to Europe for Olmo, who sent back suitable wine grape clones for the California grape and wine industry. Olmo collected the plant material that eventually became Malbec 03 and 04 on that 1951 trip.

Tracking the original material for Malbec 03 and 04 requires explanation of a three-digit numbering system apparently adopted by Olmo to label his “finds” during the plant exploration trips. When Olmo acquired grapevine material on one of his exploration trips around the world, he would ship the selections back to the United States (sometimes directly to Davis) labelled with a unique three-digit number preceded by Olmo’s name. Hewitt (Department of Plant Pathology, UC Davis) possessed the importation permit at Davis for some of the years during which Olmo collected materials. Hewitt maintained a binder in Davis showing the early Olmo imports.

The three-digit Olmo numbers appear on grapevine selections in the FPS database and in the grape indexing binders that were maintained by USDA Plant Pathologist Austin Goheen to document disease testing at FPS. Those same numbers remained attached to some of the selections through variety trials that Olmo conducted to identify and track the imported material.

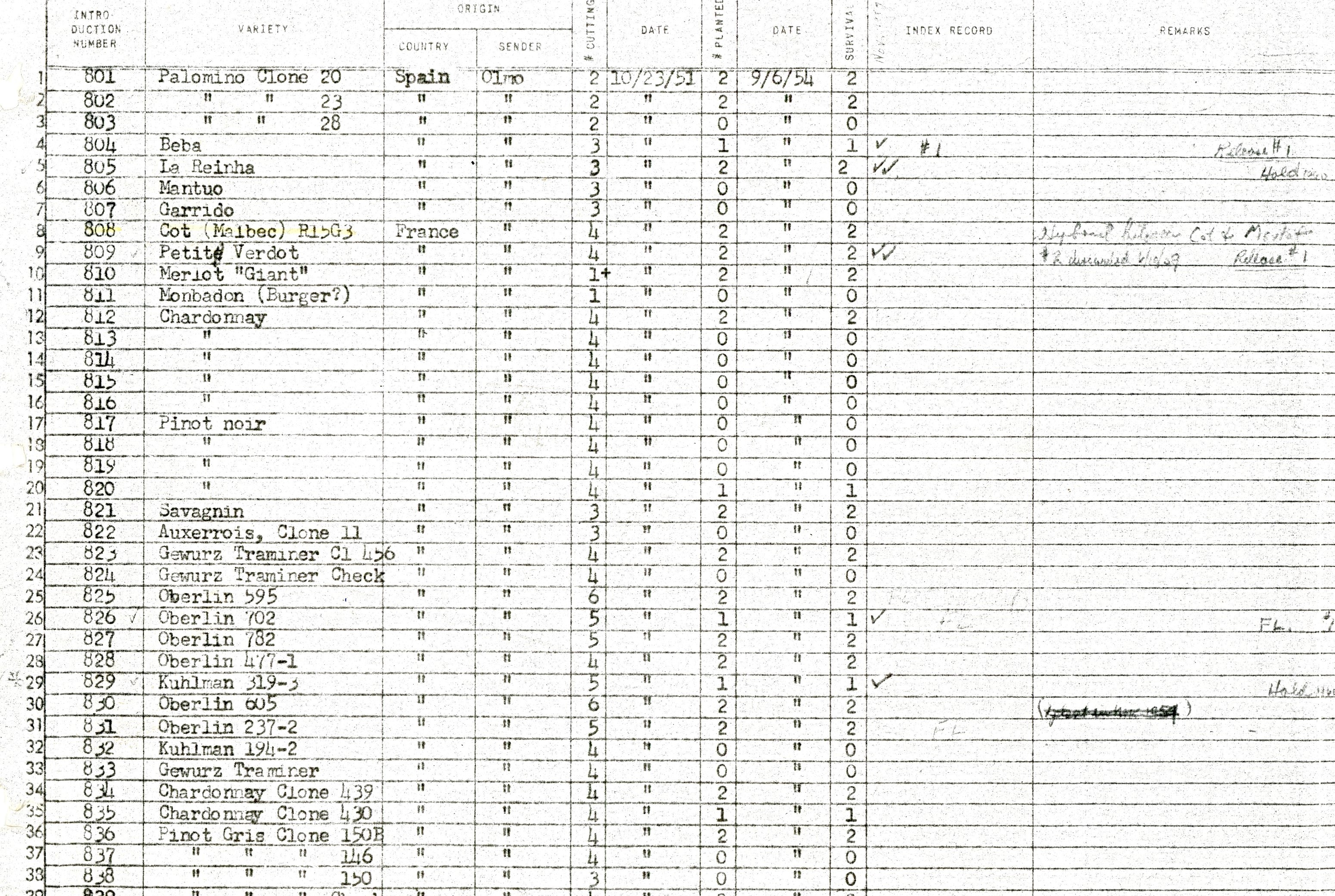

The three-digit numbering system is significant for the Malbec selections because the material that ultimately became Malbec 03 and 04 was initially identified and tracked by “number 808” from its initial appearance in importation records in Davis. Hewitt’s importation binder labelled “805-1305, Hewit’s Introductions” is one of the historical records contained in FPS files. The binder shows Olmo importations beginning in 1951; the Hewitt binder documents the date of arrival of the grape cultivar in the United States, source of the cultivars, dates of planting at Davis and release dates. There is a column containing an “introduction number”, which for some of the 1951 imports does not coincide with the USDA Plant Introduction number. The “introduction numbers” for some of the French imports sent by Olmo in 1951 were three-digit numbers beginning with an 8. The “sender” of the grapevine material was “Olmo”.

The Hewitt binder contains an entry for “Introduction number 808” with the variety name “Cot (Malbec) R15G3”, sent by Olmo from France to the U.S. in October, 1951. There is no indication in the record as to the meaning of “R15G3”. The reference could signify a vine location with a typographical error, but the record is not clear. For introduction 808, there is also a notation in the “Remarks” section of the Hewitt binder that the material is a “Hybrid between Cot and Merlot” (which share a maternal parent). The notation “Cot x Merlot” also appears in the Goheen indexing binder for the Malbec selection associated with number 808.

Entries in the FPS indexing records and Olmo’s file show that the original source of the grapevine material designated “introduction number 808-1” was Grand Ferrade in Bordeaux, France. There is a grapevine variety collection near Bordeaux at the research station of Grande Ferrade à Villanave d’Ornon, which is part of INRA’s Centre de Bordeaux-Aquitaine. In an FPS record for a Malbec clonal trial in Oakville, FPS Program Manager Curtis Alley refers to Malbec 04 as “Olmo’s Cot” and “Olmo-Bordeaux”.

The Hewitt binder indicated that the “number 808” plant material was “released” at UC Davis in 1954. It was planted in 1955 at “O.F. (Block A) r9 v3”, a location in the Old Foundation vineyard at Armstrong tract. The selection name and number of the new planting were “Cot (Malbec) 1”. The plant material at O.F. r9v3 began index testing under the number 808-1, beginning in 1958.

After the original material successfully completed the first round of index testing in 1961, it was planted in location C2 v 1-12 in the then-new FPS foundation vineyard west of Hopkins Road near the FPMS facility. Material from those vines was thereafter subjected to two different heat treatments (96 days and 103 days) in 1964-65 and eventually became Malbec FPS 03 and FPS 04, respectively. After successful completion of index testing, the heat-treated selections were planted in 1966 in the FPS foundation vineyard at locations FV E2v2 (Malbec 03) and FV E2v3 (Malbec 04).

Any doubt about the fact that the material received in 1951 was in fact pure Malbec (rather than Cot x Merlot) was resolved by professional identification of the vines at FPS. Malbec 03 and 04 were identified as Malbec by ampelographers Jean-Michel Boursiquot (1996) and M. Andrew Walker (1998). Finally, FPS scientist Gerald Dangl performed DNA analysis on Malbec 04, and its profile matched references for the Malbec/Cot cultivar. 77 Dangl, Gerald, email from Gerald Dangl, Plant Identification Lab Manager, Foundation Plant Services, to author on August 09, 2012.

Malbec 03/04 has been the second most-widely distributed Malbec “clone” at FPS, second only to Malbec FPS 09.

Malbec 06

The official source vine for Malbec 06 in the FPS database is given as “Viticulture K129 v1”, which was a location in the “Wine Grape Production” Block K. Block K was part of the UC Department of Viticulture’s vineyard in the Armstrong tract in 1949. It is probable that the Malbec vine in Block K is a successor vine several generations removed from the first vineyard installed by the Department at the “University Farm” at Davis in 1910.

Frederic T. Bioletti, the university’s first Professor and Chair of the Department of Viticulture, planned the new vineyards that were installed at the University Farm at Davis. Those vineyard plans, drawings and plant lists are in a notebook Bioletti kept around 1910. The notebook is now housed in the Olmo collection (D-280) in the Department of Special Collections at Shields Library at U.C. Davis. 78 Bioletti, F.T., “Davis: Vineyard, Maps and Plans”, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California, Davis, Olmo D-280, Box 2, folder 11.

The early vineyards planted at Davis were given numbers. The initial vineyard in the Bioletti notebook is Vineyard #1. Blocks A and B of that vineyard were designated “Selection Plots” which were planted beginning in 1910. 79 Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis, Olmo D-280, Box 23, folders 22-23. Malbec was planted in both Block A, row 35 v1-24 and Block B, row 35 v1-24. Notes on the map indicate that the plant material in those locations was from the University experiment station in Tulare. 80 Hilgard, 1890, supra, pp. 135-136. A list of vines “growing at Davis in December, 1913” showed Malbec only in Vineyard #1 (Blocks A35 and B35) at that time.

Plot D of Vineyard #1 was the Department of Viticulture’s “Collection of Vinifera Varieties”, with vine planting lists shown initially through row 39. Plot D is described beginning on page 10 of Bioletti’s notebook. Those vines appear to have been planted around 1910 or 1911. Source information for those vines was usually noted, either individually or for a group of vines. Plantings in the lower-numbered rows were usually from the Tulare Station. Malbec was not planted in the Plot D variety collection until row 46 (shown in a later entry).

After the list of vines planted in Plot D in 1911, there are in the notebook several lists that describe cuttings needed in 1911-1912 for future plantings for Plot D. There are lists of cuttings to be brought from several different locations, e.g., Woodland, Pomona, Tulare. One list is entitled “Cuttings Needed from Miscellaneous (B, FG, F)” – Berkeley, Fountain Grove, Fresno. Malbec is one of the cultivars on that “Miscellaneous” list. The source for that cultivar is noted as Fountain Grove, Santa Rosa. Malbec is not included on any of the lists of vines needed for future plantings except on the Miscellaneous List. The desired sources for the Miscellaneous List are noted in Bioletti’s handwriting. He also wanted Chenin blanc, Clairette blanche, Chardonnay, Grand noir, Listan, and Limberger from Fountain Grove.

There is reason to believe that Frederic Bioletti was familiar with the grapevine material at Fountain Grove in Sonoma since he was acquainted with the owner of the property. The settlement at Fountain Grove was originally established in 1875 by Thomas Lake Harris, a minister and poet who founded the utopian “Brotherhood of the New Life” in upstate New York. He moved to the hills near Santa Rosa in 1875 and established a new settlement of around 2,000 acres, much of which was covered by vineyards. The vineyards grew good varieties such as Cabernet and Zinfandel, and red table wine was the staple product. Harris was a colorful and controversial character who believed in a philosophical mix of socialism and mysticism and espoused unusual ideas about sex. Eventually he left Fountain Grove in 1892 and deeded the Fountain Grove property to his adopted son, Kanawe Nagasawa. Nagasawa became a respected grape grower and wine maker. He became friends with Bioletti in the process. 81 Pinney, 1989 (volume 1), supra, pp. 332-335; Anonymous (1900), “Strange Devise of Fountain Grove”, Pacific Wine & Spirit Review, vol XLIII, November 30, 1900, San Francisco, California.

In the records at Shields Library is a notebook entitled “RESISTANT VINES, Notes on Fountain Grove Vineyard, Santa Rosa, Sonoma County, 1910”, in which the Fountain Grove cultivars named above all have individual pages. The notes taken on each cultivar appear to be in the handwriting of Frederic Bioletti. He observed Malbec on “Chas. x Ber.” Rootstock [41-B]. The plants appeared to be “doing well”, although the crop was light. The berries were of irregular size, blue in color and sweet. Many of the berries were seedless. There was no graft enlargement at the union of scion and stock.

It appears that the Malbec from Fountain Grove, Santa Rosa, was ultimately planted in the Department Variety Collection at Davis in Vineyard #1, Block (Plot) D, row 46 vines 21-24. That planting was later than the original list of rows 1-39 (from the Tulare Station). A document in the Olmo files entitled “Summary of Davis Vineyard #1, July 19, 1916” designates Block D as a collection of vinifera varieties and shows Malbec plantings at locations in Block A, Block B and Block D (D46 v 21-24). 82 Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis, Olmo-D-280, Box 3, folder 46.

Tracing the source material for Malbec 06 becomes problematic by the relocation of Vineyard #1 (including Blocks A, B and D) to several new locations at the University Farm during the 1920’s. The source material for Malbec 06 can be tracked in FPS files back to a Malbec vine at location B8 in the newly relocated vineyards. Reference is also made by Curtis Alley in correspondence to Malbec 06 as being from “the old variety collection”.

83 Alley, C.J. (1978). Curtis Alley was the Program Manager of Foundation Plant Materials Service in the 1970’s. He was also an Extension Specialist at the University of California, Davis. Correspondence by Alley in FPS files in connection with the 1978-1980 Malbec clonal trials gives a history of Malbec 06 as “C6v11, old E2v1, and old variety collection”.

Old vineyard maps for the Department, indexing records at FPS and variety notes maintained by Harold Olmo show the successive locations for Malbec 06 as follows:

B8 → E104:1 (1940) → K129:1 → Malbec 06 (Hopkins FV C6:11 (1964) and E2:1 (1967)).

An ambiguity arises when the identity of the plant material at “location B8” is investigated. A small hardbacked book named “Vine Collection Davis 1932” contains drawings of the “new” vineyards, with lists of vines and locations. A map shows a diagram for “new” Vineyard VI (Blocks A and B) and Vineyard VIII (Blocks A through C) next to Hutchison Road that runs through the campus in Davis. Malbec was planted in Block B of both Vineyard VI and Vineyard VIII. 84 Vine Collection Davis 1932, Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis, Olmo D-280, Box 77, folder 17.

Malbec was planted in location B6 in Vineyard VIII. The “new” Vineyard VIII, Block B, rows 1-9 were intended to be part of a “Wine grape variety collection”, planted beginning in 1924. Malbec was planted in the new wine grape variety collection at B6 v11-12. 85 Department of Special Collections, Shields Library, UC Davis, Olmo D-280, Box 9 folder 11. A logical inference might be made that the Fountain Grove Malbec from the original Department Variety Collection in Vineyard #1 was moved to the “new” variety collection in Vineyard VIII.

Malbec was also planted in Vineyard VI at location B8. The materials available in the files at Shields Library do not contain any detail about the purpose of the new Vineyard VI. The records and vineyard maps at FPS do show that Malbec was installed in Vineyard VI sometime after 1925 in block B8, vines 1-35. There is no source information in the old maps for this planting at B8. The old records at FPS (which probably came from oral history on campus) indicate that Malbec 06 (and therefore B8) was from the “old variety collection”. That reference could support the theory of the Fountain Grove Malbec as the source. 86 Alley, C.J. (1978), supra.

The bottom line is: the most that can be stated with any confidence is that the planting in B8 was probably from either (1) the Fountain Grove Malbec from Vineyard #1, Block D, or (2) the Malbec from the Tulare Station that had been planted in Vineyard #1, Blocks A and B, in 1910. There is no information in the files at FPS or in the Olmo collection files at Shields Library that a third source of Malbec was present in the vineyards at Davis during the 1920’s.

Plant material from vine K129:1 (the successor vine to B8) initially came to FPS for index testing starting in 1956. That selection was one of the early plantings (location C2 v13-16) in the new FPS foundation vineyard west of Hopkins Road in 1962. The selection was assigned the name Malbec-2 (on the list of FPS foundation vines) and Malbec 5 (in the Goheen indexing binder), although neither of those selection numbers was ever entered in the FPS database.

Plant material from the same source vine K129:1 underwent heat treatment therapy for 63 days in 1962. It is not clear from the records whether the material that underwent heat treatment was taken from the original source vine (K129:1) or the vines in foundation vineyard location C2 v13-16 (Malbec 2/Malbec 5). However, both sources go back to vine K129:1. After successful completion of index testing, the heat-treated selection was planted as Malbec 06 in 1964 in the FPS foundation vineyard west of Hopkins Road.

Malbec 08/Malbec 12

The plant material for this selection arrived in California in March, 1966, and was sent to UC Davis by C.R.A.S.O. (Centre Recherches Agronomiques Sud-Ouest) in Pont-de-la-Maye in the Gironde region, France (USDA Plant Introduction number 312798). The import was labelled with the name “Malbec 1056”. The full name of “Malbec 1056” (also known as Cot) was “INRA-Bx 1056” which originated in the Lot region of France in Cahors vineyards. INRA-Bx 1056 was certified as French Cot 46 in 1971.

Upon arrival at Davis, the plant material was installed for a time at location K2v58 in the Old Foundation (Armstrong) vineyard and began the index testing process at FPS. The decision was made to subject the selection to heat treatment therapy for 60 days, which it underwent in 1969. After successful completion of index testing, the new heat-treated material was given the selection number Malbec 08, planted in 1975 in the FPS foundation vineyard west of Hopkins Road at location L5 v9-10.

In 1997, Malbec 08 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture disease elimination therapy to eliminate Rupestris stem pitting virus. The new material received the selection name Malbec 12 and was planted in the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2005. The selection was identified at FPS using DNA technology in 2010. Malbec 12 has also qualified for the new Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard, where it was planted in 2011.

Malbec 09

The plant material that became Malbec 09, Malbec 10 and Malbec 11 was imported to Davis from France in 1989. The shipment was part of a project sponsored by Winegrowers of California to bring important French clones to California to improve the wine industry. This effort antedated the establishment in 1997 of the ENTAV-INRA® trademark program for certified French clonal material.

In the mid-1980’s, the Oregon Winegrower Association and Oregon State University (OSU) collaborated on a project related to a mutual interest in European clonal material. David Adelsheim of Adelsheim Vineyard in Oregon and Ron Cameron at OSU worked together and successfully established relationships with viticulturists in public programs in France. The OSU program (which at that time had an importation permit for grapevines) was able to import many varieties and clones from French vineyards. Mr. Adelsheim appeared in California at a 1985 meeting of university and grape industry members and explained the OSU importation project. In response to interest from the California grape and wine industry, OSU agreed to make some of the clones available for the public collection at FPS in 1987-88. When Dr. Cameron retired from OSU, he made a special effort to ensure that FPS received all the clones from OSU.

Later, FPS was able to arrange for direct shipment of additional clones from France to FPS as part of this project, which was then sponsored by Winegrowers of California. Two Cot (Malbec) clones were sent to FPS in 1989 in one of the direct shipments sponsored by the California group. That material was the source of Malbec 09, Malbec 10 and Malbec 11.

FPS uses the words “generic French clones” for French clonal material that was sent to the United States prior to the establishment of the official ENTAV-INRA® trademark program. “Generic clones” are publicly available and are assigned an FPS selection number that is different from the reported French clone number. The source for generic French clones is indicated on the FPS database using the following language: “reported to be French clone xxx”. This language is used to distinguish the generic clonal material from trademarked clones that are certified by ENTAV (now IFV) and sent from the official French vineyards. There is no guarantee of authenticity for generic clones.

In 1989, FPS received two Malbec clones that were reported to be French Cot clones 46 and 180. The clones were sent from INRA’s Chambre’Agriculture de la Gironde in Aquitaine, France. The Chambre d’Agriculture is a type of semi-governmental agency that exists in France in each geographical area. Those agencies frequently work on clonal selection and extension work. The agency in the Gironde was one of those that performed clonal evaluation work.

The material that is reported to be French Cot clone 180 eventually became Malbec 09 at FPS. Cot 180 originated from Bordeaux vineyards in the Gironde area. 87 Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin. 2006. Catalogue officiel des variétés de vigne cultivées en France, 2ème édition, Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche-CTPS, VINIFLHOR. The material went through index testing in 1989-90 and did not receive any disease therapy or treatment. After successful completion of testing, Malbec 09 was planted in the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 1992. This selection has been the most widely-distributed Malbec selection at FPS.

Malbec 10 and 11

Malbec 10 and Malbec 11 are reported to be French Cot clone 46, which originated from Cahors vineyards in the region of southwest France near the Lot River. Both Malbec 10 and 11 underwent microshoot tip tissue culture disease elimination therapy prior to 2000. After successful completion of disease testing, Malbec 10 and Malbec 11 were planted in the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 1999 and 2000, respectively.

In France, Cot clone 46 has superior fertility and an average-to-superior level of production and sugar content. Cot clone 180 has inferior fertility and inferior-to-average level of production. 88 Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin. 2006, supra.

Malbec 22

Malbec 22 has had a long and confusing history at Foundation Plant Services. The plant material arrived in Davis in March, 1962, from the Station de Recherches Viticoles d’Arboriculture Frutière, C.R.A.S.O., in Pont-de-la-Maye, Gironde, France. The name on the imported material was “Cabernet Savagnin, CL 1563” (USDA Plant Introduction no. 279498).

FPS began disease testing the material in 1968-69, initially as Cabernet Sauvignon. The material underwent heat treatment therapy in 1966 for 105 days. Sometime during the subsequent disease testing process, the name of the plant material was changed to Merlot. After the final disease testing results were recorded in 1968, the selection was planted as Merlot 07 in 1970 in the FPS foundation vineyard.

As evidenced by a note entered in the Goheen indexing binder prior to Goheen’s retirement in 1986, someone suspected that the selection was possibly Malbec rather than Merlot. DNA testing revealed in 2000 that the selection was, in fact, Malbec. 89 Meredith, Carole, “1999-00 DNA Testing of FPMS Vines”, FPMS Grape Program Newsletter, p. 3, October 2000.

In 2006, the selection underwent microshoot tip tissue culture disease elimination therapy to clean up leafroll virus. In November of 2010, FPS changed the name to Malbec 22. Malbec 22 successfully completed 2010 Protocol disease testing necessary for qualification for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard, where it was planted in 2012. The name was then changed to Malbec 22.1.

Consultant and viticulturist Phil Freese was a Vice-President at Mondavi Winery in the 1990’s when he identified the pre-tissue culture version of what is now known as Malbec 22/22.1 for use in Mondavi and Opus One wines. Mondavi realized that the cultivar was Malbec, not Merlot, and ensured that the selection was correctly identified as such. They preferred the FPS clone to other Malbec selections and used it at Mondavi Winery. In 2012, vines of the pre-tissue culture material for Malbec 22 still existed at Mondavi in a block planted at the To Kalon vineyard in Oakville (to the west of the north field station). 90 Bosch, Daniel, Senior Viticulturist at Constellation Wines Email July 19, 2012. Personal communication with the author.

Michael Silacci, Winemaker and Director of Viticulture at Opus One, confirmed that Opus One has used the pre-tissue culture version of what is now the Malbec 22 selection in every Opus wine since 1994. They recognized the clone as Malbec (and not Merlot) using a visual identification. The Malbec clone constitutes about 1% of the Opus vineyard acreage and is only a small percentage of the Opus wine. 91 Silacci, Michael, Winemaker and Director of Viticulture, Opus One. Personal communication with author, July 20, 2012

Malbec 31

Duarte Nursery in Hughson, California, donated Malbec 31 to the public grapevine collection at FPS in 2011. The material originated from a vineyard in Palo Alto, California. After undergoing microshoot tip tissue culture treatment at FPS in 2012, Malbec 31 qualified for both the Classic Foundation Vineyard and the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard.

Cot ENTAV-INRA® 595, 596 and 598

There are three official, certified French clones for the Malbec/Cot cultivar at Foundation Plant Services. The authorized French clones for this cultivar are named Cot in the FPS foundation vineyard, to preserve the preferred French nomenclature.

The agency formerly known as The Etablissement National Technique pour l’Amelioration de la Viticulture (ENTAV) was an official agency certified by the French Ministry of Agriculture and was responsible for the management and coordination of the French national clonal selection program. ENTAV merged with ITV France in 2007; the new entity is called the Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin (IFV). IFV continues with the responsibilities formerly administered by ENTAV, including maintenance of the French national repository of accredited clones and ENTAV-INRA® authorized clone trademark to protect the official French clones internationally. Trademarked importations come directly from official French source vines and are authorized French clonal material. IFV retains the exclusive rights to control the distribution and propagation of its trademarked materials which are only available to the public from nurseries licensed by IFV.

In the French system, clonal material is subjected to extensive testing and certification. There are 16 Cot (Malbec) clones that are certified by the French Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Cot 595, 596 and 598 are from Cahors vineyards in the region of southwest France near the Lot River. The IFV catalogue states that those clones are valued for their agronomic characteristics and the quality of wines produced from the grapes. 92 Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin. 2006, supra.

Cot ENTAV-INRA® 596 came to FPS in 2000. It successfully completed disease testing and was planted in the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2003.

Cot ENTAV-INRA® 598 also came to FPS in 2000. It was planted in the Classic Foundation Vineyard in 2002 after successful completion of disease testing. This selection also underwent microshoot tip tissue culture therapy to qualify by the 2010 Protocol for planting in the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard. The tissue culture version of this selection successfully completed disease testing and was planted in Russell Ranch in 2012 as Cot ENTAV-INRA® 598.1.

IFV imported another of the official French clones, Cot ENTAV-INRA® 595, to FPS in 2012. Clone 595 originated from Cahors vineyards in the region of southwest France near the Lot River. The ENTAV catalogue indicates that the clone yields typical, fine and well-balanced wines. The original material qualified for the California Grapevine Registration & Certification Program in 2013 and for the Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard in 2016.

The ENTAV proprietary selections may be obtained through IFV licensees who sell ENTAV-INRA® grapevine material in the United States.

Argentinian Malbec at FPS

The FPS foundation vineyard currently houses many Malbec selections that originated from Argentina. All the existing FPS Malbec clones from Argentina are proprietary clones that are not available for distribution to the public, either directly from FPS or through a nursery.

Argentine Malbec clones reportedly differ in appearance from the clones from France. Some of the Argentine clones used in the fine Malbec wines were specifically selected and developed to have small berries and bunches for concentrated flavors. 93 Mount, 2012, supra, p. 235.

Malbec 13-17 are owned by a large Argentine winery. Malbec 20 and 21 are owned by a U.S. winery. It is possible that Malbec 20 and 21 might become available to the public around 2020 if they appear to be unique in some fashion.

UC Variety and Clonal Assessments

The University of California began evaluating appropriate grapes and wines for California in the 1870’s. Malbec was one of the cultivars included in the early studies because the Bordeaux cultivars were some of the first imports to the state. Clonal evaluations conducted by the university between 1966 and 2010 built upon those early observations and assessments reported by Hilgard, Amerine and Winkler.

Viticultural Characteristics

Malbec is a black grape variety that is sensitive to coulure (poor fruit set or shatter) and temperature extremes. Coulure occurs particularly with high vigor or cool weather during bloom; it can lead to low yields of 1 to 3 tons per acre. If set is good, production levels are moderate to high. The cultivar is not always easy to grow, requiring sunny and dry weather conditions. If grown in favorable conditions, Malbec is a vigorous variety adaptable to a wide range of soil types. It has large leaves and unusually strong lateral shoot growth leading to a dense canopy in the fruit zone that might interfere with grape maturation. 94 Robinson, 2006, supra, p. 421; Weber, supra, pp. 75-76; Amerine and Winkler, 1944, supra, p. 664; Wetmore, 1884, supra, Part V (Ampelography).

Ough and Alley, 1966

UC Davis Professor Cornelius Ough and Extension Specialist Curtis Alley reviewed the data on Malbec based on the work done by Hilgard, Amerine and Winkler plus their own unpublished data from research in the coastal regions of California on the “Cabernet” varieties (Malbec, Cabernet franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Ruby Cabernet, Pfeffer, and Merlot). The evaluation was limited to performance in California regions I and II (primarily coastal climates). The researchers noted that Malbec wines that underwent malolactic fermentions suffered a deficiency in acid, an excessively high pH level and deteroriation in quality. They did not recommend Malbec for planting at that time (1966). They were optimistic about a “newly acquired” Malbec clone at FPS (Malbec 08/12) that promised a heavier production level that possibly could solve the pH problem. 95 Ough, C.S. and C. J. Alley. 1966. “An Evaluation of Some Cabernet Varieties”, Wines & Vines, May, 1966, p. 23; Ough, C.S., and C.J. Alley. Undated. Cabernet-type Grapes and Wines from the Coastal Regions of California, Department of Viticulture and Enology, University of California, Davis.

UCD Clonal Trial Oakville, 1978-80

A clonal trial was conducted by Cornelius Ough and Curtis Alley on three FPS Malbec selections at UC’s Oakville Station in Napa County between 1978 and 1980. The Jaeger Family Foundation of St. Helena sponsored the clonal evaluation with the goal of locating a “superior clone of Malbec that will do well in....the North Coast area”.

The clonal material was planted at Oakville in 1976 and 1977. The budwood used in the trial was from Malbec 04, 06 and 08, and from two other non-certified clones that never entered the FPS program. In 1978 and 1979, Malbec 08 was by far the best producer in terms of tons/acre (2.83 and 4.0). In 1980, there were no significant differences in yield for the three clones, but FPS 08 had a larger-sized cluster (mean cluster weight). The researchers observed that many clusters had a large percentage of small shot berries which reduced yield, which the researchers attributed to extensive virus acquired from the rootstock used in the trial. 96 Alley, C.J. 1980. Letter from C.J. Alley to Mr. William P. Jaeger dated November 18, 1980, with results of Malbec clonal trial harvests from 1979 and 1980; Alley, C.J. 1978a. Letter from C.J. Alley to Mr. William P. Jaeger, Jr., dated November 1, 1978, containing a map of the Malbec clonal test planting and result of 1978 harvest.

UCD Clonal Trial Oakville Station, 1997-2000

University researchers studied the same three clones again at Oakville, from 1997 to 2000. Malbec 04, 06 and 08 were grafted onto rootstocks 110R and Teleki 5C and planted in 1992. Four years of data were taken.

Malbec 08 (now Malbec 12) averaged the highest yield for all yield components over the four-year period – 10.5 kg/vine total yield and 1.80 kg cluster weight. Malbec 04 was intermediate and Malbec 06 was the lowest. Yearly variation in yield occurred for all selections and was largely dependent on berries per cluster. Differences in clusters per shoot were significant and were correlated with yield. The researchers concluded that Malbec 08, although not consistent from year to year, produced enough fruit even in poor-crop years to be the most commercially viable. The ultimate recommendation was that growers plant Malbec 08, regardless of possible canopy manipulation that could make Malbec 04 and 06 perform with higher yields.

Consistent with yield results, Malbec 06 had the highest pruning and shoot weights, and Malbec 08 had the lowest. There were no differences between rootstocks in average vegetative growth, but there was a significant rootstock-clone interaction for Malbec 06. Rootstock 110R had increased yield in high crop years but did not prevent poor fruit set in low crop years.

Malbec 06 had the highest average soluble solids (23.5) and pH (3.48) at harvest, while Malbec 08 had the lowest (22.1 and 3.36). Malbec 08 averaged the lowest titratable acidities (6.9), while Malbec 04 had the highest TA (7.5). The advantage of any of the three selections regarding Brix was “very dependent on yield”. 97 Benz, M. Jason, Michael M. Anderson, Molly A. Williams, and James A. Wolpert, “Viticultural Performance of Three Malbec Clones on Two Rootstocks in Oakville, Napa Valley, California”, Am.J.Enol.Vitic. 58:2 (2007).

Wine Grape Varieties in California, 2003

A publication produced by the University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, in 2003 contains a report on the performance of the Malbec clones that were in the FPS collection at that time. The variety profiles were written by University viticulture extension specialists and underwent peer review by scientists and other qualified professionals. In the book, former Napa Viticulture Extension Specialist Edward Weber wrote that clonal selection is important for Malbec to minimize the risk of coulure. He indicated that Malbec 04 and 06 were particularly prone to poor fruit set and low yields. Malbec 08 (now Malbec 12) was consistently higher yielding but moderate in production. He wrote that Malbec 09 (French Cot 180) and 10 (French Cot 46) showed potential for a more consistent crop set. 98 Weber, Edward, “Malbec”, p. 75, Wine Grape Varieties in California, eds. Christensen, L.P., N.K. Dokoozlian, M.A. Walker, and J.A. Wolpert (University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, Oakland, CA, 2003).

UCD Clonal Trial at Kearney Agricultural Center, 2007-2010

Former UC Davis Cooperative Extension Viticulture Specialist Dr. Jim Wolpert and associate Mike Anderson completed phase 1 of field trials at UC’s Kearney Agricultural Research and Extension Center (KAREC) in Fresno County. The purpose of the trials was to evaluate viticultural characteristics (color, tannin, acid and sugar) and identify new cultivars that might grow well as varietal wines in the southern Central Valley. The trials were funded by the American Vineyard Foundation (AVF).

Phase 1 of the trials was planted in 2003 with 1103P rootstock. Malbec FPS 06 was one of the red cultivars included in that phase. Viticultural data were collected for the seasons 2007 through 2010. The commercial viability level for growers was set at yields of 8 tons per acre. Wines were made by Constellation.

Dr. Wolpert reported the following to AVF in 2011:

“The harvest composition was not the best with Malbec 06 pH creeping up close to 4, even at relatively low Brix (< 23). The low rot and good color in the wine make it a cultivar that has some promise if the yield could be improved. Industry members present at the wine tasting evaluations did not like the wine quality of Malbec at Kearney as much as they did from cooler production areas.

“Malbec is not recommended for planting in the southern Central Valley at this time, but a clonal trial might provide a more attractive selection in terms of identifying selections that could increase yield. Better fruit set should be a consideration in any future clonal trial.” 99 Wolpert, J.A. 2012. Email from Dr. J.A. Wolpert, Senior Viticulture Extension Specialist, Department of Viticulture and Enology, University of California, Davis, to author dated August 7, 2012.

In summary, the major theme of university research and observations of the Malbec grape from Hilgard’s time to the present is that the cultivar has potential in California and is worthy of further study.

Conclusion

Malbec continues to attract winemakers as both a blending and varietal wine. Acreage for the cultivar in the United States is increasing in several major wine-producing regions. Foundation Plant Services offers many healthy Malbec selections from which to choose for new plantings.